Norse Winter Spirits: Húsvættir, Draugr and more

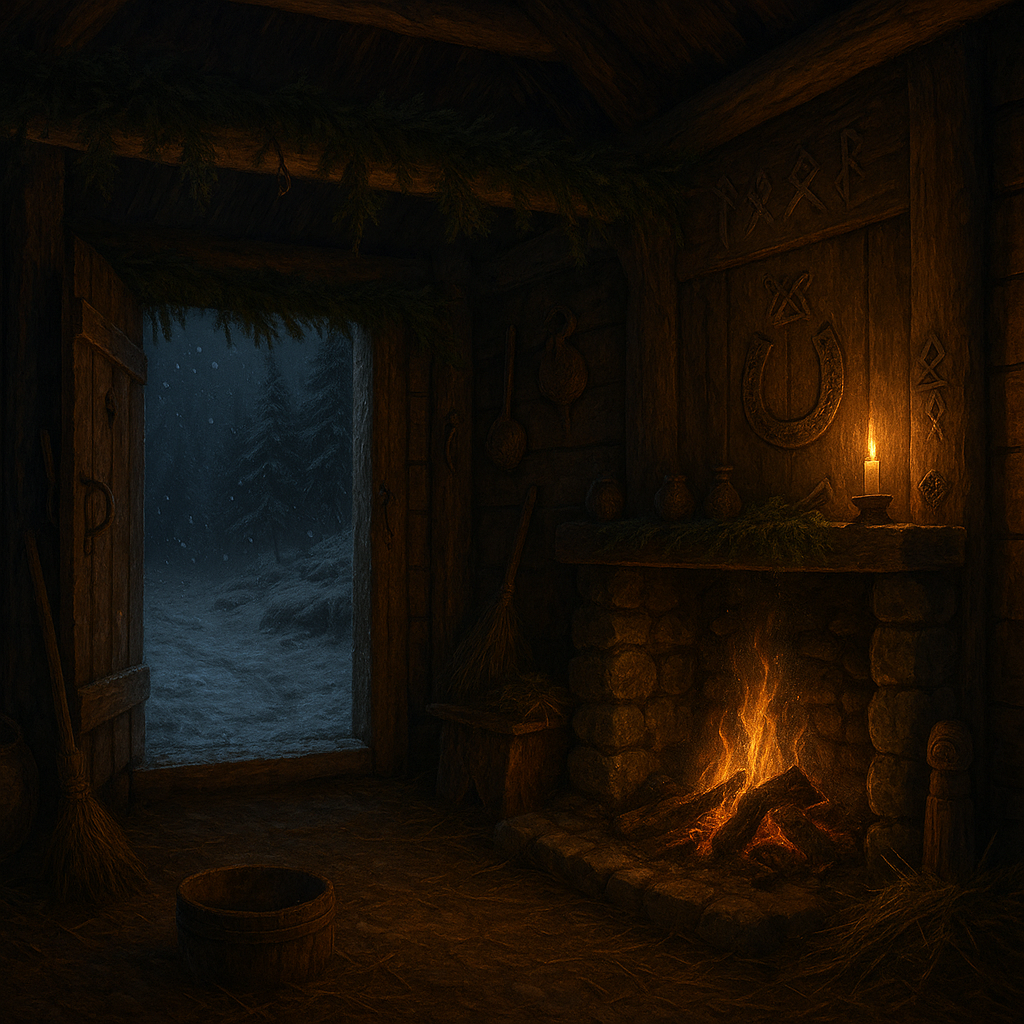

Winter in the old Norse world was more than a season. It was a presence. A long shadow that crept across the land, tightening the cold around farms, fjords and forests. When the sun dipped low and the wind carved across the ice, people felt the world shift. The boundaries grew thinner. The nights stretched deeper. And in those dark months, the North believed the unseen world drew closer than at any other time of the year.

The Norse did not look at winter simply as weather. They saw it as a time when spirits stirred. House spirits moved through the rafters. Ancestors gathered around the homestead. Elves slipped closer, bringing both blessing and danger. And above it all, on storm-winds that howled through mountain passes, the Wild Hunt thundered across the winter sky - an omen to some, a terror to others, and always a reminder that the world was far larger and more mysterious than daylight revealed.

In a time before electric lights and central heating, winter was survival. Cold meant hunger, darkness meant uncertainty, and every creak of the longhouse carried weight. But the Norse did not face these months alone. Their world was filled with beings who shared the land with them. Some were protectors. Some were fickle. Some brought luck. Others brought ill fortune or death. And all of them were thought to be more active when snow covered the earth and the living stayed indoors.

Winter was also a season of rituals. Families set out bowls of porridge for the húsvættir, the house spirits who guarded the home. Elves were honoured quietly, without outsiders present, in the old rite of the Álfablót. Doors were kept shut at certain hours, tools laid a certain way, and stories whispered by firelight warned of nights when one should not walk alone. Traditions formed a kind of protection, a way of staying in right relationship with the unseen forces that moved through the cold.

At the same time, winter brought a sense of wonder. Ancestors were thought to walk close. Dreams grew stronger. Omens sharpened. The spirits of land and lineage were not abstract ideas - they were active presences guiding, warning or haunting the living. The season marked the turning of the year, the deep silence before rebirth, a time when the living world rested and the hidden world moved.

This blog explores that winter landscape: the húsvættir who guarded the hearth, the álfar who bridged the line between ancestors and nature powers, and the Wild Hunt whose storm riders filled the northern skies with dread and awe. We will follow these beliefs from the sagas into later Scandinavian folklore, tracing how the old ideas changed yet endured, shaping winter traditions long after the ‘Viking Age’ faded.

To understand Norse winter spirits is to understand how the old North saw the world: alive, layered and full of presence. When winter came, they believed they lived not just with the elements, but with a host of spirits - some friendly, some fearsome, all woven into the deep fabric of northern life.

The Norse Spiritual Landscape: A World Alive with Unseen Beings

To understand Norse winter spirits, we first have to understand the world they inhabited. The people of the old North did not divide reality into the natural and the supernatural the way we often do today. For them, the world was layered, interconnected and alive. The visible landscape of mountains, fields, rivers and sea was only the topmost surface of a much deeper reality. Beneath and around it existed a host of beings who shaped luck, protected families, guarded places, or, at times, caused harm.

This was not superstition tacked onto daily life. It was the framework through which the Norse understood existence. Every place had its own presence, every family its own unseen allies and dangers, and every action had consequences in both worlds.

The land itself was full of persons, not people but presences. Rocks, hills, forests, valleys, lakes and even specific patches of ground could hold memories and spirits. You could offend a stretch of land by disrespect or heal a relationship with it through offerings. The Norse saw the landscape as something you lived with, not simply on. In this sense, the world was inhabited on multiple levels: humans on one, spirits on another, ancestors on another still. These layers overlapped constantly, especially in winter.

The boundary between worlds was thinner in some places than others. Howes, burial mounds, ancient cairns, crossroads, and stretches of untouched forest were known as liminal zones where the living might feel the presence of powers older than themselves. These were not simply locations on a map; they were thresholds. The Norse travelled through such places with respect, care and sometimes fear, knowing that beings who lived parallel to them might be watching.

Among these presences were the húsvættir, the house spirits who dwelled in and around the home. They were not ghosts but guardians tied to the land, the structure of the house, or the family itself. A healthy relationship with them meant safety, prosperity and protection through the long winters. A neglected or offended húsvættir could withdraw its favour, allowing misfortune or unrest to creep in. In a world where survival depended on everything going well, this relationship was taken seriously.

The álfar, another major group of beings, lived somewhere between ancestor spirits and nature spirits. Their exact nature shifts across sources, but what remains consistent is their closeness to humans. They were not distant, shining figures living in unreachable realms. They were local, tied to particular hills or family lines. People offered to them as one might offer to an honoured relative or an old, powerful neighbour. To ignore them was to upset the balance of the unseen world.

There were darker beings too. Trolls, jötnar and vetrarvættir, winter spirits connected to storms, ice, or the lonely places of the world. These beings were not necessarily evil, but they were dangerous. Winter increased their influence. The long darkness made the edges of the world feel sharper, and the unknown stronger. When the wind screamed around the longhouse or snow drifted into unnatural shapes, some felt these beings brushing close.

Even the dead were part of this spiritual landscape. Ancestors lingered near the home, sometimes protective, sometimes restless. Burial mounds were not places of abandonment but active points of connection between the living and those who had gone before. In winter, when life slowed and nights lengthened, the dead felt closer. Dreams carried more weight. Silhouettes in doorways meant more than imagination.

Above all these presences loomed the Hunt: a roving company of the dead or the divine, depending on the region, riding through winter storms. Its passage linked weather, the dead and the unseen in a single terrifying vision. People stayed indoors, kept their heads down and avoided wandering after dark, trusting that the Hunt moved according to a law older than humans.

To live in the Norse world was to live with constant awareness of these unseen layers. Winter sharpened that awareness. The cold and darkness brought the spirits into clearer focus, making the borders between their world and ours feel thin as frost on a window. For the Norse, this was not frightening so much as natural. The world was vast and full of company. Some companions were friendly, others indifferent, others hostile. But all were real, all were near, and all formed part of the great, living landscape of the North.

Húsvættir: Guardians of Home, Hearth and Farm

In the Norse world, a home was never only timber, earth and thatch. It was a living place, shared not just with family and livestock but with unseen beings who formed an essential part of the household’s life. These beings were the húsvættir - the house wights, spirits tied to the dwelling, the land beneath it and the people who lived there. They were not abstract ideas. They were treated as real members of the household, deserving of respect, offerings and careful attention, especially through the long winter months.

The húsvættir were among the most intimate spirits in Norse belief. While gods were distant and mighty and ancestors hovered at the edges of dream and ritual, the house spirits were constant companions. They swept unseen through rafters, watched from shadowed corners, guarded thresholds and kept a quiet eye on everything from the fire’s health to the well being of the animals. A satisfied house spirit could ensure smooth seasons, safe nights and steady luck. A neglected or insulted one could sour milk, tangle work, unsettle sleep or bring a creeping unease to the whole farm.

Their exact nature is never fully defined in the sources, which is typical of Norse belief. The old writers did not classify húsvættir, nor did they explain their origins. Instead, they treated them as a simple fact of life, a presence so well understood culturally that formal description was unnecessary. Some traditions imagined them as small, humanoid beings capable of appearing to the household. Others viewed them more like forces or presences, part of the land itself. Some were tied to the building; others were tied to the clan that lived there.

What is clear is their role: protectors and caretakers. The húsvættir maintained the unseen balance of the home. They watched over livestock, especially during winter when animals were kept indoors. They guarded grain stores from spoilage, protected tools from harm and ensured the family’s luck was not drained or disturbed. When winter storms howled and snow piled against the doors, people believed these spirits worked quietly beside them, holding the household together against the cold.

Respect was essential. The relationship with húsvættir was reciprocal. Offerings were made to acknowledge their presence — a bowl of porridge, a splash of milk, a piece of bread left in a quiet corner. Such offerings were not meant as worship, but as hospitality, the same courtesy shown to any honoured guest. A house was considered healthy when the húsvættir were content, and unhealthy when they were not. If misfortune struck repeatedly, or if livestock sickened without clear cause, some would interpret it as a sign that the spirits were displeased and needed appeasement.

Wintered in communities paid even closer attention to the húsvættir. With daylight scarce and storms frequent, the boundaries between the living and the unseen grew thinner. During Yule, the great midwinter festival, many families made special offerings to the house spirits, ensuring their favour for the coming year. These acts kept harmony between worlds during the darkest season, when protection was needed most.

The húsvættir were not uniformly gentle. They could be temperamental, even vengeful when disrespected. A householder who acted with arrogance, neglected the home, mistreated animals or wasted food could provoke the spirit’s displeasure. This could manifest in small disturbances (tools misplaced, sudden cold spots, restless dreams) or in larger misfortunes that tore at the fabric of the household. These warnings were taken seriously. The Norse believed that living well meant tending to the unseen as carefully as the seen.

Their role extended beyond the literal home. Barns, stables, byres and storage sheds each had their own spirits, forming a network of guardians across the farmstead. In harsh winters, when survival depended on the careful management of food stores and the health of animals, these spirits were seen as active allies in the struggle against hunger, cold and misfortune. Their protection was not mystical but practical - a presence that watched, warned and supported.

The húsvættir also connected the living household to the deeper history of the land. A house spirit might predate the family, tied to earlier settlements or to the natural character of the place. When families moved or built new structures, they often sought the goodwill of whatever spirit already lingered there. Respecting the húsvættir meant acknowledging that humans were temporary residents in a world filled with older, quieter beings.

Later Scandinavian folklore preserves this belief with remarkable clarity. The tomte or nisse (the small, bearded, cap wearing guardian) is the folk-memory of the húsvættir. He tends barns, watches livestock, protects sleepers and expects offerings at Yule. His temper, helpfulness and fierce loyalty all echo the older stories of house wights. This survival into modern tradition shows how deeply rooted the belief was, and how thoroughly it shaped the way northern peoples understood home.

In the Norse mind, a household was never alone. Every firelit hall, every barn filled with wintering animals, every storehouse packed with grain, had its unseen keeper. The húsvættir formed the first circle of protection around the family, sharing the hardships of winter and the quiet rhythms of daily life. They were the guardians of the hearth, the silent watchers of the night, and the oldest companions of those who dared to carve out a life in the cold, demanding lands of the North.

Winter Customs for the House Spirits: Offerings, Respect and Warnings

For the Norse, winter was not only a test of strength and endurance; it was a season of ritual. As nights lengthened and frost took hold of the land, the relationship between humans and their húsvættir (the house spirits) became even more important. These spirits were believed to work tirelessly through the darkest months, protecting the home, livestock and family fortune. In return, they expected acknowledgment, respect and offerings. Failing to keep this bond alive could invite misfortune when the household needed stability most.

Winter customs for the húsvættir were woven into everyday life, carried out with quiet reverence rather than grand ceremony. A simple bowl of porridge left on a windowsill, a clean corner kept in the barn, or a respectful gesture before entering the byre could carry great spiritual weight. These acts were not empty traditions; they were rooted in the belief that harmony with the unseen world was essential for survival.

One of the most important winter rites was the offering of food, especially at Yule. Families set aside a portion of the finest porridge (often prepared with butter or cream, luxuries in winter) and placed it where the house spirit was thought to dwell. Sometimes this offering was left in the loft, sometimes on the hearth, sometimes in the barn, depending on local custom. The practice appears across the Norse and later Scandinavian world, showing how deeply the idea of feeding the house spirit was embedded in winter tradition.

The logic behind the offering was simple: a well-fed spirit meant a well fed household. A house spirit that felt honoured would guard the home from harm, keep animals healthy, ensure tools did not break at critical moments, and maintain a steady sense of luck. A neglected one might withdraw, allowing illness, misfortune or unexplained troubles to creep in. The Norse did not see these outcomes as supernatural punishments but as the natural consequences of failing to respect the unseen partners who shared their world.

Cleanliness and order were also forms of respect. Sweeping the floors before bed, keeping the barn tidy and storing tools properly were not just practical habits but spiritual courtesies. A clean house meant a peaceful spirit. A cluttered, chaotic home was seen as inhospitable, even insulting. The húsvættir, like many spirits in old belief, were thought to value neatness, careful work and respectful behaviour. In some tales, they even helped with chores when pleased, finishing tasks left undone or tending animals at night.

Winter warnings were just as important as winter offerings. Certain actions were avoided because they were believed to offend or disturb the house spirits during the tense, vulnerable months of cold and darkness. People avoided shouting indoors or slamming doors unnecessarily. They refrained from mocking invisible beings or telling disrespectful stories about spirits. Tools were not left lying around in a way that might cause injury. Livestock were treated gently, because harming an animal under a house spirit’s care was one of the fastest ways to provoke its anger.

Even small gestures mattered. Some households did not spin wool at night in winter, fearing it would tangle the spirit’s patience. Others avoided whistling indoors, which was believed to summon unwelcome forces or irritate the house wight. Fires were tended carefully, for the hearth was often considered the seat of the spirit’s presence. A dying fire in the middle of winter was both a physical danger and a spiritual omen.

The húsvættir were also included in communal winter practices. When families feasted at Yule, a portion of every dish might be set aside for the spirit. When ale was brewed, the first taste was sometimes poured out as an offering. When the family greeted the turning of the year, they often did so with quiet prayers or gestures of thanks to the spirit who had watched over them through the darkening months.

These customs did not fade with the end of the Viking Age. They continued into later Scandinavian folklore almost unchanged. The tomte or nisse (the small, cap wearing guardian of the farm) still expects his bowl of Christmas porridge, and tales warn that neglecting him leads to injury, spoiled food or animals mysteriously falling ill. These stories are the surviving echo of Norse winter rites, showing how the old belief persisted long after Christianity reshaped other parts of life.

At its heart, winter customs for the húsvættir were about relationship. They expressed gratitude, respect and awareness that humans did not face winter alone. The spirits of the home were allies, protectors and sometimes stern overseers. By honouring them, families affirmed their place in a world where the visible and invisible worked together for survival.

For the Norse, life in winter was a partnership - between kin, land, ancestors and the quiet beings who moved in the shadows of the hearth. And through offerings, careful behaviour and mindful respect, that partnership was renewed each year, keeping the home warm and guarded as the dark pressed in.

Winter as a Thin Season: Why Spirits Were Closer in the Dark Months

To the Norse, winter was not simply a stretch of cold weather. It was a shift in the nature of reality. As the days shortened and the world grew quieter, they believed the boundaries between the living and the unseen became thinner. The dead walked nearer. House spirits stirred more strongly. Land wights moved with greater freedom. Even the gods were thought to cast longer shadows in the dark months. Winter was a season of nearness, when the otherworld breathed against the edges of human life.

This belief was rooted in lived experience. Winter brought silence. Fields lay fallow. Rivers slowed under ice. Birds vanished. Travel became dangerous, often impossible. Families stayed indoors for long stretches, cut off from neighbours except for rare visits. In this hush, every sound grew sharper. A creak in the rafters carried weight. A shifting shadow in the barn meant more than a trick of the light. The world felt closer, more attentive, more alive.

People of the North did not see this heightened presence as imagination. They understood it as a change in the balance between worlds. The spirits were always there (in fields, hearths, mounds and mountains) but in winter, when human activity slowed and nature itself seemed to pull inward, the unseen had more room to move.

Darkness played a central role. These were people who lived far from the equator, where winter swallows the daylight. In Iceland and parts of Scandinavia, the sun barely rose or disappeared entirely behind mountains for weeks at a time. Darkness was not symbolic; it was a constant companion. And darkness, in old belief, was the natural element of spirits. Not evil, not hostile, simply belonging to them. The unseen was not separated from the night - it was part of it.

With darkness came cold, and cold itself was a force. Frost cracked wood, howled through chimneys, turned breath to steam and numbed fingers in minutes. The Norse linked cold with the realm of giants, the deep North, and the primal forces that shaped the world before the gods. When the winds raged around the farmstead at night, it was easy to imagine something older than humans moving in the storm. Winter weather carried personality - not a metaphorical personality, but an active presence.

This made winter a season when spirits of all kinds were believed to pass more freely. House spirits were alert, roaming the halls, checking the stores, guarding the barn from dangers both mundane and supernatural. Land wights drew nearer to homesteads, watching how people treated the snow-laden earth. Ancestors stood closer to the living, sometimes appearing in dreams, sometimes felt as a shift in the atmosphere. Those who died violently or without proper rites were thought to be especially restless in winter, when the veil between their world and ours thinned.

Even the dead in their burial mounds were believed to stir during the darkest nights. Mounds were often snow-covered landmarks, silent but heavy with presence. People avoided passing them after dark, not out of superstition but from inherited instinct. Many sagas describe ghosts walking more frequently in winter - not because the stories needed drama, but because that is when people genuinely expected them to appear.

Yule marked the peak of this thin season. It was the turning of the year and a time when the dead were believed to walk freely. Families prepared extra seats at the table, left food out, and kept fires burning long into the night to honour the unseen guests. Yule was not just a celebration; it was a negotiation with the otherworld, a moment when the living acknowledged the presence of ancestors, spirits and wandering beings.

The Wild Hunt, with its storm born riders, was said to roam most fiercely in winter. The dark, windy nights made the perfect backdrop for this dangerous procession. People listened for unusual sounds in the sky - a sudden rush of wind, dogs barking in terror, distant voices carried on the storm. These signs were not ignored. They were warnings that the world was open and the borders thin.

Winter was also a time of prophecy. Dreams grew sharper and more vivid. The Norse believed that in the quiet of the long nights, when the mind drifted more easily, the unseen could speak. Dreams of ancestors, omens or strange encounters were taken more seriously in winter than at any other time. The sagas reflect this belief with frequent winter dream-visions that reveal hidden truths or foretell danger.

This thinning of the world’s boundaries was not viewed as frightening by default. It was simply the natural order. Winter was the season when the spirits played a larger role in daily life, and humans had to move with greater awareness. People showed respect: they kept their homes tidy, honoured the house spirits, avoided unnecessary risks and paid attention to signs. They saw winter not as an enemy but as a time of heightened connection.

The Norse knew that winter stripped life down to essentials - food, warmth, shelter, kin. In this stripped down world, the unseen companions who shared the land became more visible in their own way. Winter reminded people that life operated on many layers, some visible, some not, and that survival depended on acknowledging all of them.

In this sense, winter was the season of truth. The season when one felt the full closeness of the land, the ancestors and the spirits who shaped the rhythms of northern life. It was a thin season not because it was empty, but because it was full - full of presence, memory, silence and the voices of the unseen.

If you want, I can now generate an image for this section or move on to the next topic, such as Álfar in the Dark Season: Ancestors, Nature Spirits and Winter Blessings.

Protecting the Home: Winter Wards, Rituals and Folk Practices

In the Norse world, winter was not simply weather to endure. It was a force, an active presence that pressed against the walls of the home. Storms howled like voices, darkness pooled in the corners of rooms, and the stillness outside carried a weight that felt older than human memory. In this environment, a household’s safety depended not only on wood, fire and food, but on spiritual protection. Through winter, the Norse relied on a collection of wards, customs and small rituals to keep their homes in balance with the unseen world.

These practices varied between regions and families, but they shared a common purpose: to maintain peace between the living and the spirits who moved more freely during the dark months. Winter was the season when the húsvættir watched the closest, when the álfar grew near, and when the restless dead might wander if neglected or disturbed. A home that respected the unseen world was considered healthier, safer and more fortunate than one that did not.

One of the simplest but most important winter protections was fire. The hearth was not only a source of warmth; it was a boundary-marker, a living guardian at the heart of the home. People kept it burning steadily on the longest nights, believing that spirits respected a tended flame. A dying hearth was a sign of vulnerability, a moment when protective presence might falter. Families sometimes added scented herbs or pieces of evergreen to the fire during winter rites, strengthening the hearth’s symbolic boundary.

Doors and thresholds were also carefully watched. These were liminal spaces, places where the outside world touched the safety of the interior. Many households placed protective objects near doorways: iron tools, carved wooden symbols, animal bones, or small stones believed to hold luck. Iron in particular was seen as a barrier against harmful spirits. It wasn’t waved about dramatically but tucked quietly into shadowed places - a knife in a beam, an iron key hung above a door, a nail hammered into a threshold. These small gestures were part of daily practical magic.

Winter rituals for the land spirits also played a role in household protection. Even in frozen months, people offered scraps of food, grain or ale to the spirits who guarded the land around the farm. Keeping the land wights on good terms meant keeping the pathways to and from the home spiritually safe. A neglected land spirit could allow wandering beings to come too close, or let misfortune slip into the boundaries of the property.

At Yule, the rituals intensified. Families cleaned the entire house - not only for comfort but to signal to the unseen that the home was ready to receive good fortune and ward off ill. Some spread fresh straw on the floor, creating a soft, sacred space for both guests and spirits. Others made circles from evergreen branches or hung greenery above doors as a symbol of life enduring through the dark season. These were not decorations in the modern sense but living wards meant to strengthen the home’s spiritual defenses.

Food offerings formed another key part of winter protection. A portion of the Yule feast was given to the húsvættir — often porridge with butter, ale, or a slice of meat. This offering wasn’t merely symbolic. It was believed to renew the bond between the spirit and the family, prompting the húsvættir to work even harder to safeguard the home, livestock and supplies. Later Scandinavian folklore preserves this almost unchanged: the tomte expects his Christmas porridge, and woe to the farmer who forgets it.

Spoken rituals existed too, though rarely formalised. A simple verbal greeting to the spirits of the land when stepping outside on a cold night. A quiet acknowledgement before taking food from the storage loft. A whispered request for protection while tending animals in the barn. These were not prayers in the Christian sense but respectful recognitions of the unseen beings who shared the world.

Some winter wards were more hidden and personal. A farmer might carry a specific stone in his pocket during storms, believing it held luck. A woman might tie a small charm into her clothing to ward off troublesome spirits during the longest nights. Tools belonging to ancestors were often kept near the door, partly as a memory and partly as spiritual reinforcement: the dead, in their wisdom, continued to guard the living.

Children were also taught winter cautions. They learned not to whistle indoors, not to run outside after dark, and not to look directly into deep snowdrifts where hidden beings might lurk. They were told to close doors gently and never to mock the invisible. These rules were not fear-based but respectful; they maintained harmony with forces that the Norse believed were simply part of life.

Winter protections extended to the animals as well. Livestock were blessed, groomed and fed carefully. Some families placed charms in the stables to keep harmful spirits away. The barn was seen as a place where the spirit world pressed particularly close, especially during the coldest nights. A calm barn was a good omen; restless animals were a sign that something unseen was moving nearby.

Through all these practices, one theme remained constant: respect. The Norse did not imagine themselves as fighting the spirit world. They lived alongside it, sometimes negotiating, sometimes appeasing, always aware that winter required cooperation between seen and unseen partners. Protection came not from aggression but from attentiveness, ritual care and the recognition that life’s boundaries were more porous in the dark months.

To protect the home in winter was to honour the spirits that shared it, keep peace with the land beneath it, and stay alert to the subtle signs that life extended far beyond the walls of the longhouse. In the coldest season, survival depended on warmth, food and vigilance - but also on the quiet rituals that held the household together against the night.

Ghosts, Draugar and Restless Dead in Winter Traditions

Winter was the season when the dead came closest to the living. This was not superstition in the modern sense; it was accepted reality in the Norse world. The long dark, the deep cold, and the stillness of the land created conditions in which the presence of the dead felt nearer, more immediate, and more active. The sagas and folklore consistently depict the winter months as the time when hauntings grew stronger, revenants stirred in their mounds, and the boundary between worlds thinned enough for the dead to walk.

The Norse did not speak of ghosts as faint, transparent figures drifting through rooms. Their ghosts were beings with weight, will and personality. Winter was the backdrop for many of the most vivid encounters with the dead, not because writers needed drama, but because that was when people truly expected such things to happen.

One reason winter amplified the presence of the dead was the quiet. Farms fell into silence under snow. Doors were shut for long stretches. Animals huddled in barns, and the landscape outside lay frozen and still. Any disturbance in such a world (a creak in the rafters, footsteps outside, a shadow crossing a firelit wall) was instantly noticeable. The Norse interpreted these moments not as tricks of the senses but as signs that something unseen had wandered close.

The draugr, the again-walker, was especially feared in winter. Cold preserved bodies unnaturally well, and frozen ground made burial difficult. Corpses might lie unburied for weeks, a circumstance believed to increase the likelihood of them rising. Stories often describe draugar emerging from their mounds during the darkest nights, driven by greed, rage or unfinished business. Their breath was said to freeze in the air, their skin cold as stone, their strength greater than any living man. A stormy winter night, with wind howling across the fields, was their natural element.

In Grettis saga, Glámr dies on a snow covered hillside during Yule. His body is found frozen stiff and swollen with an eerie corpse-light, as though the cold itself had reshaped him. When he rises, he becomes one of the most terrifying revenants in Norse literature. Winter is not just the backdrop to his return - it is the reason for it. His death in the dark season, unblessed and unburied, sets the stage for his haunting. Villagers hear him stamping across rooftops, rattling doors, and screaming through the night winds. His presence is tied to the season, a reminder that cold and darkness gave the dead power.

The restless dead in Eyrbyggja saga also appear during the winter months. After a series of deaths, the farm at Fróðá becomes overwhelmed by ghostly activity: drowned men dripping seawater, women appearing at the door, the dead sitting silently at the longhouse benches. These ghosts are not violent, but they drain the strength of the living, bringing sickness, fear and misfortune. This haunting only stabilises when proper rites are performed, suggesting the importance of ritual order during the dark months.

Winter also held danger for those buried in mounds. The dead were believed to guard their graves, especially if treasure or personal items were interred with them. The mound itself became more active in winter. Snow made the shape of the burial hill more distinct, and the cold amplified the sense of presence hovering around it. People avoided passing burial mounds at night, fearing that the haugbúi within might rise to challenge trespassers. In some stories, lights flicker over the mounds in winter - signs of the dead stirring or guarding their possessions.

Not all winter ghosts were physical revenants. Many appeared in dreams, a form of contact that the Norse took very seriously. The long nights created the perfect space for vivid, symbolic or direct encounters with the dead. Ancestors often appeared warning of danger, asking for proper burial rites or offering guidance. These dream visits were believed to be genuine; the dead crossed through the thin winter veil to speak.

Sudden chills, cold patches in the longhouse, or animals behaving strangely were interpreted as signs of the dead passing close by. A horse refusing to enter a barn on a winter night was not seen as stubbornness but as a warning. A dog howling at nothing in the dark meant something unseen was moving through the yard. Livestock were considered particularly sensitive to spirits, and their behaviour was watched carefully.

Winter deaths were considered especially risky. Those who died from cold or storms, or those who perished suddenly without preparation, were more likely to become restless. A person who died afraid, angry or unfinished might not settle easily. Their spirit could linger around the home or drift through the snowy landscape. A sudden knock on the door on a winter night could be interpreted as a dead relative seeking warmth or acknowledgment. Failing to answer might offend them; answering wrongly might invite them in too strongly.

Imported Christian ideas eventually blended with older beliefs, creating winter traditions involving ghosts seeking prayers, absolution or memorial rites. But the older Norse view remained underneath: the dead wandered because the season allowed it. Winter belonged partly to them.

The Wild Hunt, storm-riders sweeping through the sky, was also connected to the wandering dead. Some said the Hunt was made of warriors or ancestors restless in the dark months. Hearing the Hunt in the distance - a sudden rush of wind, strange cries carried through the air—was a sign to stay indoors, cover your face, and show no curiosity. Winter nights were full of such warnings.

In the Norse imagination, the dead were never fully gone. But in winter, they were close enough to touch the edges of the living world. Some came with love, some with grief, some with rage, and some with no intent at all - simply drifting like shadows in the long northern night. Winter was their season, and the living moved through it with respect, caution and the knowledge that the world was shared with more than the eye could see.

The Crossover of Christian and Pagan Winter Beliefs

When Christianity spread through the North, it did not sweep away older winter traditions. Instead, it settled over them like a new layer of snow, softening their edges but leaving the shapes beneath still visible. In the long dark months, where the old beliefs held the strongest grip, Christian and pagan ideas blended into something uniquely Scandinavian - a winter spirituality that spoke two languages at once.

The early Church faced a challenge in the North. Winter was already loaded with meaning: a time when spirits walked, ancestors drew near, and powerful forces stirred in the night winds. Rather than attempt to erase these beliefs, Christian missionaries often adjusted their teachings to sit alongside them. As a result, many winter customs from the ‘Viking Age’ survived well into the Christian centuries, transformed but recognisable.

One of the clearest examples is the Yule season. Yule was an ancient festival tied to the dark of winter, the turning of the year, and the honouring of spirits - gods, ancestors and land-wights alike. When Christianity arrived, it overlaid this festival with Christmas. But under the hymns and church bells, the old practices endured. Families still lit extra candles and fires to strengthen the boundary between living and dead. Offerings were still left in quiet corners of the house or barn, even if people no longer publicly called them gifts for spirits. The act remained, the name changed.

Christian winter saints absorbed traits of older beings. Saint Nicholas, Saint Lucia, and various local holy figures often took on roles previously held by elves, disir or house spirits. They became guardians of hearth and home, protectors of travellers, bringers of winter luck or light. People prayed to them in winter for many of the same reasons they once honoured the húsvættir.

Likewise, winter ghosts did not disappear under Christianity. Instead, their nature shifted. The dead who wandered in winter were sometimes reinterpreted as souls in Purgatory - restless not because they guarded treasure or clung to anger, but because they needed prayers to speed their journey toward heaven. Yet the behaviour of these spirits remained strikingly similar to the older draugar: they appeared in dreams, walked familiar routes, knocked on doors at night, and carried emotional weight from their life. The explanation changed; the pattern endured.

The Wild Hunt provides one of the most fascinating cases of crossover belief. Before Christianity, the Hunt was often tied to Odin or to ancestral spirits riding through the storm. Under Christian influence, the riders were sometimes reimagined as damned souls or a procession led by a cursed figure such as Herod or even the Devil himself. But the signs remained the same: storms roaring through the sky, ghostly riders heard in the wind, and the warning to stay indoors when the Hunt passed by. The identity changed, but the fear and awe did not.

Certain rituals were quietly converted rather than removed. Household protections once meant for land spirits became prayers to the Holy Spirit or to saints. Charms carved for protection against draugar were replaced by crosses or holy symbols, though the function remained: to keep something unseen at bay during the dark months. People blessed their barns, animals and doorways - now with church rites, but with the same winter logic behind them.

Even the idea of winter as a thin season survived. Christian chroniclers in medieval Scandinavia recorded with surprise how commonly people reported seeing spirits, ghosts or ancestors during winter nights, especially around Christmas. Some priests accepted these encounters as visions or warnings from the dead; others condemned them as illusions or temptations. Yet the people themselves continued to treat winter as the time when the veil between worlds was weakest.

Dreams, too, held their old significance. The Norse believed the dead could visit the living in dreams most easily in winter, and this belief continued long into the Christian era. A dream of a dead relative during the twelve nights of Christmas might be interpreted as a request for mass offerings, almsgiving, or prayer. But the structure of the experience (the dead coming close at the darkest time) remained unchanged.

This blending created a winter worldview that was neither wholly pagan nor fully Christian. It was something in between: a living tradition shaped by two spiritual systems at once. A person might go to church on Christmas morning, then return home to quietly leave a bowl of porridge in the barn for the house spirit. They might believe in the Christian afterlife, yet still avoid burial mounds at night. They might pray to God for protection while also hanging a piece of iron in the doorway out of habit.

The crossover of beliefs did not represent confusion but adaptation. Winter in the North demanded respect, caution and spiritual awareness. Whether the dead were explained by pagan lore or Christian doctrine mattered less than the experience itself: the sense that, in winter, unseen forces moved closer. In this blended worldview, the supernatural was not rejected or feared outright; it was understood as part of the season’s nature.

In the end, Christian and pagan winter beliefs merged not because people abandoned the old ways, but because winter itself held too much meaning to be reshaped by any one religion. The dark season had shaped lives for centuries - with its storms, silence, spirits and shadows — and it continued to shape them through the Middle Ages and beyond.

Scandinavian Folklore Echoes: Nisse, Tomtar and the Hidden Folk

When the ‘Viking Age’ faded and the medieval centuries took shape, the old beliefs didn’t vanish. They shifted, softened, and continued in the language of folk tradition. In the North, stories rarely die; they change their clothing. The húsvættir, álfar and land spirits of earlier centuries lived on in new forms, and nowhere is this clearer than in the enduring figures of the nisse, tomtar and the hidden folk.

Across rural Scandinavia, long after Christianity became dominant, people still spoke of small, powerful beings who watched over the farmstead. They were not angels or demons. They were not ghosts. They were descendants of the old Norse spirits, reshaped into new names but recognisable in their habits, temperaments and winter presence.

The nisse and tomte (the Norwegian and Swedish names) were the most prominent of these figures. They were described as small, human like beings who lived in barns, lofts or behind the hearth. Their size varied depending on the region: some were said to be no taller than a child, others about the height of a grown man’s waist. They were often imagined with a long beard and wearing simple clothing, sometimes with a pointed red cap in later artistic tradition. But these details are later folklore; in the oldest accounts, they are simply the unseen guardians of the homestead.

Their behaviour echoes the húsvættir of earlier belief. They guarded the house, tended animals at night, prevented accidents, and ensured good luck on the farm. But like the Norse house spirits, they demanded respect. A family that kept a tidy home, treated animals well, and left offerings would enjoy their protection. A household that neglected or insulted them risked misfortune. Cows would go dry, tools would break inexplicably, or noise would disturb the nights. These consequences were not framed as punishments so much as the natural withdrawal of spiritual support.

Winter was the season when the nisse and tomtar were at their most active. The long nights made their presence feel stronger, and the Yule season became the time when families honoured them most directly. A bowl of porridge (traditionally with a generous pat of butter) was left in the barn or loft on Christmas Eve. This was not a casual custom but a household duty. Forgetting the porridge was one of the great taboos in Scandinavian winter folklore. A slighted nisse could grow furious, sometimes causing chaos around the farm or even leaving entirely, taking the family’s luck with him.

These winter offerings were echoes of much older Norse rites. The practice of leaving food for the house spirits is documented across the medieval period and clearly continues traditions from the Viking Age. The change is not in the act itself but in the language around it. Instead of húsvættir or house-wights, families now spoke of the tomte. The spirit remained the same; only the name shifted.

The hidden folk (the huldrefolk of Norway, the vittra of northern Sweden, the huldufólk of Iceland) also preserve layers of older belief. These beings lived in hills, rocks, forests and mountains, moving unseen through the land. They were not necessarily dangerous, but they were powerful, proud and easily offended. The Norse álfar (a complex blend of ancestor spirits, land powers and nature beings) survived in these tales, though transformed by time.

In winter, the hidden folk were believed to travel more often. Families avoided disturbing certain hills or stones during the seasons of snow and frost, believing the hidden ones walked closest to human paths when the land was still. Some stories warn farmers not to build barns or sheds too near particular rocks where the vittra were said to pass. Accidents, strange noises or sudden illnesses were interpreted as signs that the hidden folk had been disturbed.

The domesticated Christmas elf of modern Scandinavian imagery (cheerful, tiny and harmless) is a late transformation of a being once treated with genuine respect and caution. Earlier tomte and nisse were powerful, unpredictable and deeply entwined with the rhythm of winter. They were not toys or decorations; they were guardians of home and land, spirits with their own pride and expectations.

Some traditions even show the nisse as a shape-shifter or a master of illusions, abilities matching the hidden folk. Folk tales describe them borrowing tools, tending livestock with supernatural skill, or playing tricks on those who disrespected them. Others portray them as ancestral in nature, as though the spirits of the dead sometimes became guardians of their old homes. This echoes the Norse belief that the hamingja, the family’s luck, could continue after death and remain tied to the homestead.

The winter connection persisted strongly. Nisse and tomtar were said to roam the farm at night during the coldest weeks, checking doors, livestock, grain stores and tools. In some parts of Norway, families left out a lantern on winter nights so the farm spirit could walk in the light. In Sweden, children were told not to spy on the tomte during Yule, for fear of angering him and causing misfortune. These warnings mirror earlier Norse cautions about not disrespecting the unseen world during the dark season.

Even in the Christian era, many families believed that homes without a tomte were unlucky. A spirit free household was vulnerable - not haunted, but unprotected. People spoke of moving house spirits with them when they left a farm, or of a tomte refusing to leave and blessing the new owners instead. These stories reflect ancient ideas about house spirits as deeply tied to place, lineage and winter survival.

By the time Scandinavian folklore was collected in the nineteenth century, the nisse and tomte had already softened in the popular imagination, but the core remained: a being who was close to the family, active in winter, and connected deeply to the land, the dead, and the rhythm of the seasons.

In these later traditions, we hear the echoes of the Norse world: a world where winter thinned the veil, where spirits walked among the living, and where respect for the unseen shaped daily life. The nisse, tomtar and hidden folk are not relics of superstition. They are the last visible threads of an older spiritual fabric, carrying hints of how the North once understood its winters - not as empty, silent months, but as a time when the world grew crowded with more than human presence.

Modern Interpretations of Norse Winter Spirits

In the modern world, where winter means electric lights, central heating and paved roads, it would be easy to assume that the old winter spirits have faded into irrelevance. Yet they persist - not as literal figures stalking the snow covered fields, but as ideas, symbols and quiet intuitions that still influence how people in the North think about the dark season. The spirits may have changed their form, but the landscape that birthed them remains, and with it, the sense that winter carries something deeper than cold and weather.

Today, interest in Norse winter spirits often emerges through folk custom, revived traditions, and the growing cultural fascination with pre-Christian beliefs. Some people look to húsvættir and tomtar as symbols of home protection and ancestral continuity. Others reinterpret the álfar and the hidden folk as metaphors for nature’s unseen forces. Still others explore draugar and restless winter dead as ways of understanding psychological states: grief, family trauma, or the heaviness that often comes with long, dark months.

One of the strongest threads in modern interpretation is the role of winter as a liminal time. Even now, the season brings stillness, reflection and a sense of isolation. Many people find that their dreams grow more vivid in winter, their emotions stronger, their intuition sharper. In this way, winter continues to mirror the old belief that the boundaries between worlds become thinner. People may no longer speak of the Wild Hunt passing overhead, but they still recognise the strange energy of winter storms, the way the wind seems to carry voices, or the way silence settles heavily on the land.

The figure of the tomte or nisse is perhaps the most widely recognised modern descendant of Norse winter spirits. In Scandinavian countries, he appears on cards, decorations and festival displays - often softened into a friendly, whimsical figure with a pointed hat and round nose. But beneath the cute appearance lies the older belief: a guardian of the home, a watcher of winter nights, a being who commands respect. Many families still leave out food for him at Christmas, unaware that they are participating in a tradition thousands of years old. This practice has become cultural rather than spiritual, yet it reflects a deep continuity of winter customs.

In modern Pagan and Heathen communities, winter spirits are often understood as expressions of seasonal energy. Practitioners honour house spirits as part of maintaining a spiritually healthy home. They acknowledge land spirits as partners in living respectfully on the land. They see ancestors as especially present during the winter months, continuing the ancient sense of winter as a time of closeness between the living and the dead. These interpretations do not seek to replicate the past exactly, but to adapt its underlying principles to contemporary life.

The Wild Hunt, too, attracts modern reinterpretations. Some see it as a symbol of winter chaos - a reminder that nature retains a wildness that humans cannot tame. Others understand it psychologically, as a metaphor for overwhelming forces in life: grief, fear, transformation or the disruption of old patterns. Some reconnect with its ancestral aspects, viewing the Hunt as a procession of the dead, a symbolic reminder of lineage and the passage of time. Even those who do not believe in literal spirit-riders find meaning in the image of a storm that carries something more than wind.

Ghosts and revenants have also taken on new life in modern thought. Scholars view draugar as expressions of social anxiety: the fear of improper burial, unresolved conflict or the consequences of a troubled life. Folklorists study them as cultural memories, showing how deeply the North connected winter with the presence of the dead. In popular culture, draugar appear in games, films and literature, often exaggerated but still carrying echoes of their saga origins: cold, heavy, relentless, and tied to emotional unrest.

Nature based interpretations see winter spirits as reflections of the environment itself. In this view, húsvættir represent the spirit of the home - the feeling of safety, warmth and continuity that people invest in their living spaces. Álfar reflect the beauty and danger of nature, particularly during winter, when landscapes turn both still and harsh. Winter ghosts represent the psychological effects of darkness, isolation and memory. Nature, in a sense, becomes the spirit-world that the Norse once saw so clearly.

There is also a growing awareness of how these beliefs shaped cultural practices. Winter hospitality, the emphasis on keeping the home warm and well-lit, and the Scandinavian tradition of gathering together during the dark months all carry faint echoes of the older worldview. Even the Nordic love of candles in winter can be traced back, in part, to the deep need to keep darkness at bay - not just for comfort, but to hold the unseen world at a respectful distance.

In modern Scandinavian culture, the idea that winter is a special, almost sacred season still endures. People speak of the quiet magic of snow-covered forests, the eerie calm of midwinter nights, and the feeling that the world becomes more introspective during the coldest months. Whether consciously or not, many still sense that winter carries a spiritual dimension - a thinning of the world, a deepening of awareness, a closeness with ancestors and memory.

The old spirits have not vanished. They have simply changed shape, becoming symbols, traditions, stories and feelings embedded in northern life. The nisse still watches over the barn in Christmas stories. The Wild Hunt still races through popular imagination when winter storms howl. The hidden folk still populate folk tales told to children. And even in cities lit by electricity and insulated from cold, people still feel that winter asks them to move more gently, more thoughtfully, as if they share the season with something unseen.

Modern interpretations do not need to recreate the past literally. Instead, they honour the enduring truth behind the old beliefs: that winter is more than weather, and that the world feels different when darkness grows deep. The spirits of winter may no longer be feared as they once were, but their presence lives on in the stories, traditions and instincts that continue to shape northern life.

The North’s Dark Months and the Spirit World’s Unbroken Thread

For the people of the old North, winter was not merely a season. It was an atmosphere, a shift in the world’s rhythm, a great turning inward of both land and spirit. As daylight faded and snow settled across fields and forests, the North became a quieter place - not lifeless, but expectant. Beneath that silence, people believed, the unseen world stirred more boldly. Winter’s darkness was not empty. It was full.

In the long dark months, when the sun barely crested the horizon and storms rolled in from the sea, Norse families lived close together in halls thick with warmth, smoke and the soft glow of firelight. But beyond the walls lay a vast, black landscape where wind screamed like voices and shadows stretched into strange shapes. It was in this atmosphere that the old conviction deepened: that winter brought the spirit world closer, thinning the boundary between the living and the unseen.

This belief did not disappear with time. It carried forward through centuries of folklore, customs and quiet intuition. Even today, the north holds a sense that winter is different, that something ancient lingers in the cold.

At the heart of this feeling was the understanding that winter pressed people into reflection. The land paused, the animals retreated, and human life slowed into a more contemplative pattern. In that stillness, memories surfaced, ancestors felt nearer, and dreams grew sharper and stranger. The North knew that silence is not just absence; it is a space that invites other presences to be heard.

Winter was also the season when the gods themselves were imagined to walk differently. Odin’s Wild Hunt rode through snow storms, sweeping across the sky like a roaring surge of wind and hooves. House spirits watched more intently, and land spirits were thought to move closer to the firelight for warmth. The dead, especially those loosely tied to their burial mounds or to the lives they left behind, were believed to wander more freely. This was not a frightening thought by default. It was simply part of how the world worked.

Winter’s hardships (hunger, sickness, isolation) made spiritual closeness feel both comforting and dangerous. A helpful húsvættir might safeguard the home, warn of trouble or bless the winter stores. A restless draugr or unhappy ancestor could bring misfortune or illness if ignored. In this sense, the people of the North did not separate practical survival from spiritual awareness. Their world demanded a relationship with both.

The unbroken thread of winter belief runs through the old sagas as much as it does through later folklore. In stories, winter is the time when revenants rise, the time when the Wild Hunt gathers its riders, the time when elves and hidden folk pass through human farms, the time when dreams become prophecies. The stories are not random. They reflect a mindset shaped by centuries of living in a landscape that transforms radically each year.

And though the old cosmology has long faded, the instinct remains. Many modern Northerners still light candles throughout the winter months, filling their homes with warmth and small circles of light. They speak of the deep quiet of snow-covered forests, the eerie calm of midwinter nights, and the feeling that winter holds secrets that summer never reveals. These feelings are not modern inventions; they are cultural memories shaped over a thousand years.

The thread that connects past and present is not belief in the literal spirits themselves, but in the winter mood that inspired them. The sense that the world becomes both larger and smaller at once - vast in darkness, intimate in closeness. The sense that winter asks you to listen differently. The sense that the season carries weight, meaning and presence.

Winter, for the Norse, was a time when the world turned its face toward the hidden realms. And even now, with electric light to beat back the dark and modern comforts to dull the cold, people still feel something old stirring beneath the surface of the season. The spirit world may no longer be spoken of openly, but the thread remains unbroken: a quiet awareness, a shiver in the dark, a sense that winter invites us to stand a little closer to the unseen.