How Fate and Free Will Worked Together in Norse Belief

The old North did not see life as random or chaotic. Nor did it imagine destiny as a rigid script that robbed people of choice. Instead, the Norse lived inside a tension: a world where the shape of a life was laid down long before birth, yet every choice, every action, every moment of courage or cowardice added weight to that shape. Fate and free will were not opposites. They were partners in the weaving of a person’s story.

For the Norse, fate was not simply something that happened to you. It was something you belonged to. Something you inherited, carried, contributed to and eventually passed on. A person arrived in the world already shaped by the deeds of ancestors, the strength or weakness of their family’s luck, and the deep patterns set by the Norns at the Well of Urd. But within that frame lay endless choices: how to meet challenges, how to carry honour, how to respond to fear, how to build a name that would remain bright long after death.

The Norse did not pretend that choice could erase fate. No saga hero escapes doom by being clever. No king rewrites prophecy by accident. Yet within the sagas we see people constantly wrestling with the tension between what cannot be changed and what must be chosen. A prophecy might set the broad arc of a life, but the tone of that life (its dignity, courage, shame or greatness) was carved by the person living it. Fate gave the shape. Deeds gave the colour.

This belief appears everywhere in the old stories. Odin himself seeks knowledge of fate, not because he hopes to defy it but because even the highest god stands beneath its authority. Heroes like Sigurd, Grettir and Helgi carry doom from birth, yet they still act fiercely, boldly, refusing to let the manner of their death define the meaning of their life. Even ordinary people in the sagas make decisions shaped by awareness of their orlog, the deep law of consequence that binds past to future. They take dream omens seriously. They weigh honour against desire. They listen for the quiet push of inherited fortune. And yet they fight, choose, love and act as though their choice matters - because it does.

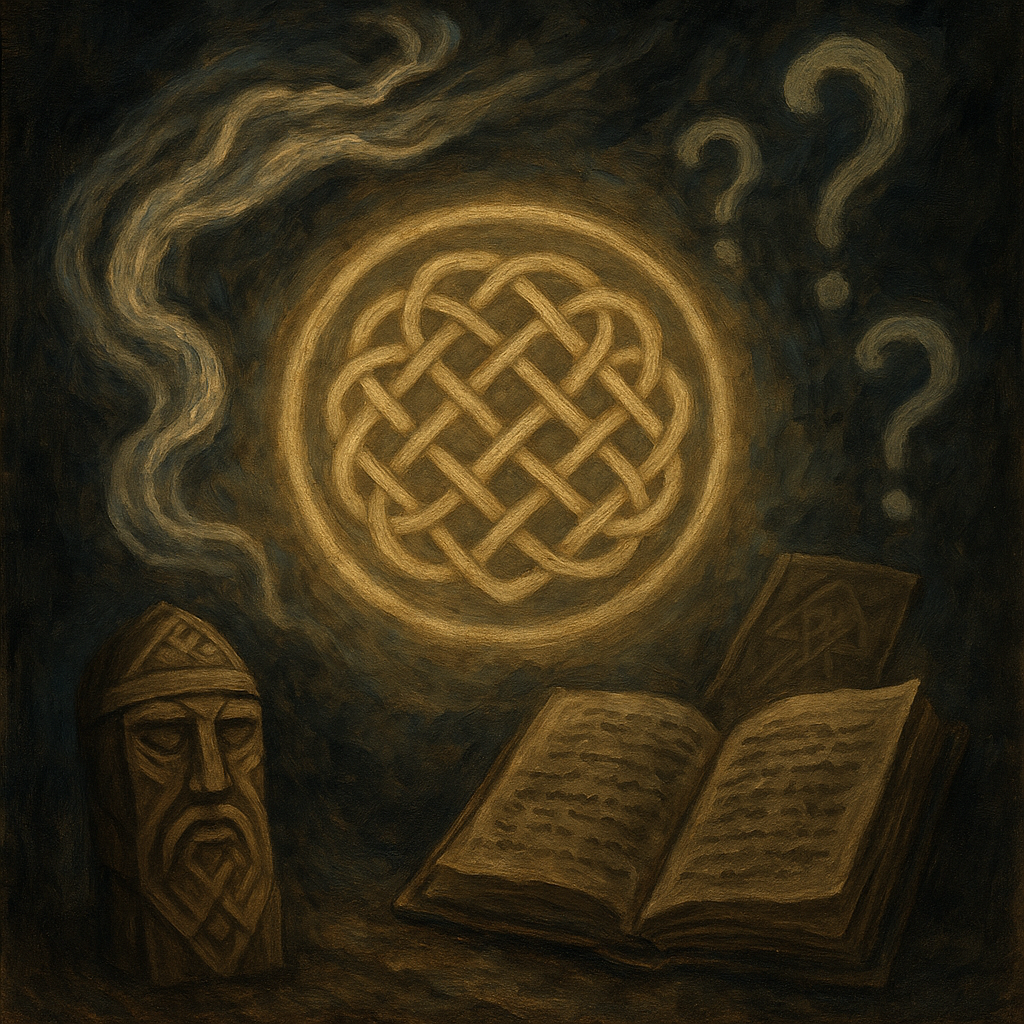

In Norse thought, fate is not a straight line but a web. Every life is a thread within it. Some threads are long, some short. Some pass through joy, others through hardship. Some are pulled by ancestors long buried, others by forces hidden in land or lineage. But each thread has its own colour, its own strength, its own story - shaped equally by what is given and what is chosen.

Understanding this worldview is essential if we want to understand the sagas, the myths, or even the daily life of those who lived in the shadow of the northern sky. It is the key to understanding how a people could face death with calm, how they took omens seriously but still acted boldly, how they believed the future held shape without ever believing themselves powerless.

To explore Norse fate is to explore the heart of their culture: a culture that valued courage, because courage was the one way a person could meet their destiny with dignity. A culture that honoured reputation, because the name you left behind mattered more than the length of your life. A culture that saw the world as layered, interconnected and full of unseen forces, where everything from ancestral luck to land spirits played a part in the unfolding of one’s fate.

What follows is a journey through that worldview: the meaning of orlog, the weaving of the Norns, the role of hamingja and wyrd, the limits and possibilities of choice, and the way sagas reveal a world where destiny is both fixed and fluid. A world where people walked with fate at their back, not as prisoners, but as participants in a story larger than themselves.

A world where fate and free will were not rivals, but two halves of one truth.

What the Norse Meant by Fate

When we speak of fate in the Norse world, we are not talking about a simple prediction of the future or a rigid script that dictates every action. The Norse idea of fate was layered, living and rooted in the very structure of reality. Fate was not just something that happened; it was something that existed before anything else, woven into the world from its first moments. To the Norse, fate was the deep pattern beneath existence, shaping the life of gods, humans and spirits alike.

The Norse did not use a single word for fate. Instead, they used several terms, each describing a different aspect of how destiny worked. Wyrd, from older Germanic roots, expressed the idea of things becoming what they must become. It was the unfolding of events as they naturally emerged from what had already happened. Fate in this sense was not arbitrary. It was the consequence of all things that came before, stretching back into time so ancient that not even the gods remembered its beginning.

Another term, orlog, referred to the deep law or primal layer of fate laid down at the roots of creation. Orlog was set before the birth of an individual, even before the shaping of the gods, and it could not be broken. It was the foundation stone of a person’s life: the family they were born into, the strengths or burdens they inherited, the broad outline of the path they were meant to walk. Orlog was not personal choice; it was the structure in which choice happened.

Fate was also tied to the Norns, the mysterious weavers who carved the lines of life. Urd, Verdandi and Skuld were the most famous, but they were only three among many. Their names reflect the nature of fate: what has happened, what is happening, and what is coming into being. Fate was not a single moment fixed in time but a continuous flow of past, present and future interacting and shaping each other. The Norns did not dictate thoughts or micromanage decisions. They set the conditions, the framework, the possibilities and the limits.

This meant that fate was not fatalistic. The Norse did not believe that every action was predetermined. Instead, they believed that the shape of a life was set, but how a person filled that shape depended on their own will, character and effort. A man might be fated to die young, but he could die well or die badly. A hero might be destined to fight in a doomed battle, but he could fight with honour or cowardice. These choices mattered. They added meaning and weight to the thread of life. Fate wasn’t there to rob humans of agency. It existed to give their choices purpose.

Fate also extended beyond the individual. A person carried the fate of their family and ancestors. The Norse believed that actions rippled across generations. A broken oath might curse descendants. A great act of courage might strengthen the family’s future. Ancestral luck, or hamingja, was part of a person’s destiny and could grow or diminish through deeds. Fate was communal. It lived in bloodlines, in clans, in the reputation and memory people carried.

Even the gods were subject to fate. Ragnarok is foretold, and no god, not even Odin, can prevent it. Instead of despairing, the gods act with urgency. They gather knowledge, forge alliances, train warriors and prepare for the coming storm. Their fate is fixed, but their actions still matter. This divine example taught humans that fate did not remove responsibility. It sharpened it.

Dreams, omens and prophecies in the sagas often reveal hints of fate. But these hints do not reduce life to helplessness. Rather, they help people understand the shape of what is coming, allowing them to prepare or respond with dignity. To know one’s fate was not to surrender; it was to step into life with clarity.

When someone ignored fate, the sagas often show their life twisting into disaster. When someone met fate with acceptance and courage, they were remembered with honour. This illustrates another key part of the Norse concept of fate: it was moral, not in terms of good or evil, but in terms of reputation. How one lived mattered more than how long one lived.

In the end, fate to the Norse was the deep rhythm of the world. It was the riverbed through which the waters of life flowed. One could not change the shape of the river, but one could choose how to navigate it. Fate gave structure. Choice gave meaning.

To understand this is to understand the Norse worldview itself: a world where destiny is powerful but not tyrannical, where humans are neither puppets nor masters, but participants in a cosmic pattern older and deeper than memory.

Orlog: The Deep Law Beneath All Things

To understand how fate truly functioned in the Norse mind, we have to look beneath the surface of prophecies, omens and saga foretellings and go to the foundation beneath it all: orlog. This concept is one of the oldest and most mysterious in the Norse worldview, a word that does not translate cleanly into modern languages because it describes something more fundamental than destiny or chance. Orlog is the deep law, the underlying pattern that shapes existence, carrying the weight of everything that ever happened and everything that must happen due to what has already been set in motion.

The word orlog literally means something like primal layers or original law. It refers to the first laws laid down in the earliest moments of creation, when the cosmos was still forming, long before gods, giants or humans took their places. These laws were not written commandments or moral rules but the structural forces that govern how events unfold. Orlog is not something the gods sit around debating. It is something they themselves stand beneath. Even Odin, the most knowledgeable and far-sighted of the gods, cannot rewrite orlog. He seeks understanding of it, not authority over it.

Orlog is not fate in the sense of a fixed script. It is more like the shape of a riverbed. It directs the flow of life, giving it channels and boundaries, but within that shape the water still moves freely, carving and shifting in small ways. Every person is born into a set of conditions shaped by their family, their ancestors, their land, their inherited luck and the events that occurred before their birth. These conditions form the orlog of their life. They are not shackles, but starting points.

What makes orlog unique is that it is cumulative. It is built from everything that has happened before. Each deed, each choice, each oath, each act of courage or betrayal adds another layer to the structure. Orlog is not a distant cosmic decree. It is history made into law. It grows and shifts with time, shaped by the weight of actions both individual and communal. A person inherits their family’s orlog. A clan inherits the orlog of its ancestors. A community inherits the orlog of its land and its past. Even the gods carry ancient debts and consequences that shape their future.

Because orlog is layered from past actions, it cannot be undone. One cannot erase what has been done, or its place in the pattern. But one can add to it, strengthen it or weaken it, influence how the next layers will settle. This is where human choice enters the picture. The Norse did not believe that you could escape orlog. But they did believe you could work with it, shape its future direction, or even transform how your descendants would inherit it. This is why honour mattered so much. Honourable actions added strength and clarity to a family’s orlog. Dishonour added weight, confusion or weakness.

The Norns are the keepers of orlog. They do not invent it; they maintain it. At the Well of Urd they carve runes, set laws and shape the threads of time according to what has already been laid down. Their work is not arbitrary. They do not decide a person’s fate out of whim. They interpret and enforce the structure that already exists. In this way, orlog is not merely cosmic law but cosmic memory. It is the accumulated story of the universe given form.

In the sagas, orlog reveals itself through the inevitability of certain events. A prophecy is not magic predicting a random future. It is a glimpse into the unfolding of orlog. When a seeress tells a king he will die in battle, she is reading the shape of his life, the weight of his ancestors, the decisions he has made, the omens surrounding him and the direction of the thread he walks. She is not binding him to something new; she is recognising what is already in motion.

This worldview allowed the Norse to hold two truths at once: the future is shaped by deep forces, and yet individual choices still matter. A man may be destined to face death on a certain day, but how he meets that day (bravely, shamefully, wisely, foolishly) will affect the legacy he leaves behind, the honour of his name and the orlog his descendants inherit. In this sense, orlog gives meaning to human deeds. If nothing mattered, courage would be pointless. If everything were predetermined, courage would be unnecessary. The Norse believed neither. They lived in a world where courage made all the difference within the larger frame of inevitability.

Orlog is also connected to luck, or hamingja. A person with strong ancestral luck has a powerful orlog behind them, a line of deeds and honourable acts that push their life toward success. A person whose ancestors broke oaths or acted dishonourably may inherit a weakened orlog, making their path heavier. Yet even then, they can improve it through their own deeds, adding new layers of strength.

In daily life, orlog shaped everything: fortunes in war, the health of a family, the rise or fall of a farmstead, the outcome of journeys and even the behaviour of land spirits or ancestors. People did not assume events were random. They believed events reflected deeper patterns, some from long before they were born. Understanding this did not make them passive. It made them attentive. They watched for signs, listened to dreams, sought advice from wise women and tried to act in harmony with the unseen forces shaping their lives.

In the Norse world, orlog was the deep heartbeat of existence. It was the law beneath all things. Not a judge, not a deity, not a punishment, but the pattern of reality itself. To know orlog was to understand the world. To act well within its structure was the essence of living with wisdom.

And so, fate to the Norse was never a prison. It was a framework. A story already in motion. A pattern woven long before, into which each person added their own colours and their own strength, knowing that nothing is erased, everything leaves an imprint, and the deep law beneath all things is always being written, layer by layer, deed by deed.

Read more about orlog here >

Wyrd and the Weaving of Consequences

Wyrd is one of the oldest and most elusive concepts in the northern tradition. The word survives most clearly in Old English, but the idea is much older and deeply rooted in the shared Germanic worldview that the Norse inherited. Wyrd does not mean fate in the rigid, predetermined sense. It means the becoming of things, the way events unfold from what has already been set in motion. Wyrd is not a single moment or a fixed endpoint. It is the ongoing process by which past actions shape the present and the present shapes the future.

To understand wyrd, imagine life not as a straight line but as an ever growing weave. Every deed is a thread thrown into the loom. Once woven, it cannot be removed. It can be crossed over, built upon or contrasted by new threads, but never undone. Wyrd is the total pattern as it forms, moment by moment, life by life, action by action. It is the living fabric of cause and consequence.

This is why wyrd has sometimes been translated as that which happens or that which has come to pass. It refers to the momentum of events, shaped by everything that has occurred before. The Norse and their Germanic kin did not imagine the future as a blank canvas. They saw it as a tapestry with countless threads already laid down, each one influencing the direction of the next. A man’s decisions, the oaths of his ancestors, the luck of his family, the landscape he lived in, the battles fought before his birth, even the dealings of gods and spirits all formed part of his wyrd.

The Norns themselves are tied to this concept. Urd represents what has become, Verdandi what is becoming, and Skuld what shall come from that becoming. This trinity reflects wyrd perfectly: the future is shaped by the present, and the present is shaped by the past. Nothing is arbitrary. Nothing stands alone. Every action leaves a trace that bends the path ahead.

In this sense, wyrd is not something imposed from above. It rises from within the world itself. It emerges from the sum of all interactions, all choices and all consequences. Even the gods are woven into wyrd. They do not float above the pattern; they help create it. Their deeds, wars, bargains, mistakes and triumphs become threads just as human actions do. This was a worldview where nothing escaped the pull of consequence.

Wyrd is also connected to memory, both personal and communal. What is remembered continues to influence the present. What is forgotten loses power. A family with a long line of honourable ancestors carries strong wyrd because their deeds are remembered and repeated in stories, strengthening the living thread. A family weighed down by betrayal or shame carries a more difficult wyrd, because memory itself has shaped their reputation and future chances. In Norse culture, to have a bright name was to have a bright wyrd.

This does not mean that wyrd removes agency. Quite the opposite. Wyrd gives context and meaning to choice. If nothing mattered, wyrd would not exist. If everything were predetermined, choice would be pointless. Instead, wyrd shows how each action joins the weaving. A person cannot change the threads already laid down, but they can choose what they add to the pattern. They can strengthen or weaken their luck. They can heal a family’s troubled weave or deepen its problems. They can meet their challenges with courage or run from them, altering how future threads will lie.

In battles described in the sagas, characters often speak of wyrd as a living force. When their fate turns, they say wyrd has shifted or wyrd has taken hold. This does not mean they see themselves as powerless. It means they acknowledge that the pattern has grown too heavy to resist, shaped by many forces beyond their single will. Yet even then, their responses (bravery, loyalty, defiance) still matter. Wyrd decides the moment; the warrior decides the manner.

Wyrd also explains why prophecies in the sagas feel inevitable but not oppressive. A prophecy is a glimpse into the shape of wyrd, not a command. It shows the direction in which the threads are already pulling. When heroes try to escape prophecy, they often end up fulfilling it precisely because the pattern was already woven beneath them. Their attempts to break it simply add more threads that strengthen its path.

In daily life, wyrd shaped everything from family fortune to unexpected disaster. A sudden stroke of luck was not random; it was the blossoming of a long thread laid down by ancestors. A misfortune might be seen as the natural consequence of forgotten oaths or older wrongs. Life made sense not because all events were good, but because all events had roots.

Wyrd was the living flow of those roots.

In the Norse worldview, wyrd and orlog together create the full picture of fate. Orlog is the foundational layer, the deep law. Wyrd is the unfolding, the movement, the weaving of all threads into the story of the world. One is the bedrock. The other is the river. One gives structure. The other gives motion.

Taken together, they form a worldview where destiny is neither rigid nor chaotic, but an organic, intertwined process. A world where every action echoes across time, and every life is a weaving in a tapestry that began long before birth and will continue long after death.

Read more about wyrd here >

The Role of the Norns in Setting Life’s Shape

They stand at the centre of everything the old North believed about destiny, consequence and the unfolding of a life. Yet they are not simple figures. They are not three neat goddesses carved into myth for decorative effect. They are ancient, mysterious beings whose work shapes the world at every level, from the fall of kings to the birth of a single child. Their presence in the myths is brief, but their influence is vast.

The Norns appear beside the Well of Urd, one of the deepest and most sacred places in Norse cosmology. This well lies beneath the root of Yggdrasil, the world tree, where all things meet: the realms of gods, giants, humans and the dead. It is here that the Norns tend the tree, draw water, lay laws and carve runes that mark the course of time. Their work is older than the gods. It begins before memory, before stories, before the ordering of the world. When the gods first gather to shape the cosmos, the Norns are already there.

Their names reflect their function. Urd is what has become. Verdandi is what is becoming. Skuld is what shall come from what is now unfolding. They are not three separate fates working in isolation. They are three faces of the same process: past feeding into present, present feeding into future. They maintain the flow of time itself, the continuous weaving of consequence that defines existence.

But these three are not alone. The lore tells us that there are many Norns, countless in number, some divine, some elven, some dwarf-born, each with different powers and responsibilities. Some attend births. Some guard families. Some shape the fate of kingdoms. Some bring blessing and protection. Others bring hardship or doom. This variety shows that being a Norn is not a matter of species but of role. A Norn is anyone, of any origin, whose function is to shape fate within the grand pattern of the world.

The Norns do not dictate every detail of a person’s life. Their work is not micromanagement. They do not choose what a person eats for breakfast or how they behave in a quarrel. Instead, they lay down the structural lines: the broad shape of a life, the limits and possibilities, the inherited qualities, the length of a lifespan, the challenges likely to arise, the strengths or flaws rooted in ancestry. In other words, they set the pattern in which choice happens.

The sagas tell us that at a person’s birth, the Norns come to lay down the lot of that life. Sometimes their gift is long and prosperous. Sometimes it is short or troubled. Sometimes disagreements among the Norns lead to a complicated or mixed fate. This moment at birth is when the shape of a life is defined, the point at which a person’s orlog (the deep law of their existence) receives its initial form.

But once that shape is set, the Norns step back. They do not interfere in daily choice. They do not follow a person through life correcting their decisions. They are architects, not puppeteers. The building they design can be lived in honourably or poorly. The structure stands, but the person determines how they fill it.

The Norns also influence the fate of larger things: families, bloodlines, cultures and even the gods themselves. When they carve runes at the Well of Urd, they are shaping the deep currents that guide the world’s unfolding. Ragnarok, the fate of the gods, is part of their domain. Even Odin bows before their knowledge. He seeks wisdom from them not because he hopes to change their decrees, but because he wishes to understand the shape of the future so he can act wisely within it.

This humility before fate is central to the Norse worldview. If the highest god cannot outrun what the Norns mark out, neither can humans. But this does not create despair. Instead, it creates clarity. Life becomes meaningful because each person must meet the shape given to them with courage, effort and integrity. The Norns set the conditions. Humans fill them with character.

In this sense, the Norns are the bridge between orlog and wyrd. Orlog is the deep law, the primal structure of destiny. Wyrd is the ongoing weaving of consequences. The Norns connect the two. They carve the initial law and ensure that the unfolding remains true to its roots. They are not creators of fate but interpreters and enforcers of the pattern already inherent in existence.

The Norse did not pray to the Norns in hope of favours. They did not bargain with them or seek to alter their decrees. The Norns were beyond such negotiation. They were not benevolent or malevolent. They were inevitable. Their work was necessary, the foundation of order in a world where everything is connected by invisible threads of cause and consequence.

To the Norse, the Norns were not simply mythic figures. They were the unseen forces that made life coherent. They were the silent hands marking the beginning of each person’s story, the keepers of cosmic balance, the guardians of time’s flow. Their work shaped the destiny of gods and humans alike, reminding everyone that while we may not choose the shape of our life, we choose how we walk within it.

Layers of the Self: Soul Parts That Shape Destiny

One of the most important keys to understanding Norse fate is understanding what the Norse believed a person actually was. Unlike many later religious systems, the Norse did not imagine the soul as a single, unified essence that leaves the body at death and travels to one afterlife. Instead, a person was made of several parts, each with its own nature, its own strength, and its own destiny. These parts could separate, linger, travel, be inherited or even outlast the physical life. Because the self was layered, fate was layered too.

A person was not a simple being but a collection of forces, some tied to the mind, some to the body, some to ancestry and some to the unseen world. Each layer played a role in shaping character, luck, destiny and the way one’s life unfolded. Each part also contributed to how the dead continued to influence the living.

The hugr was one of the most important layers. It referred to the inner mind, intention, will and emotional force. The hugr could travel outside the body in dreams, trances or visions. In the sagas, the hugr of a dead person often appears to loved ones as a warning or message. Because the hugr was strong and mobile, it played a direct role in fate. A courageous hugr shaped a strong destiny. A fearful or disturbed hugr could lead a person into hardship. The hugr was the force that pushed a person to act, to choose, to stand firm or to falter. Fate did not override the hugr. Fate met the hugr.

Closely tied to fate was the hamingja, the family’s stored luck. Hamingja was not personal fortune like rolling a good number on dice. It was inherited power, built through generations of honourable deeds, courage, generosity and achievement. A family with strong hamingja moved through the world with greater protection, prosperity and opportunities. This luck could pass from parent to child, and in some cases from a dying person to a chosen heir. Because hamingja was inherited but could also be strengthened or damaged by personal deeds, it formed one of the strongest links between fate and free will. A person with poor inherited luck could improve it through honourable living. A person with great luck could squander it. Fate was not fixed; it carried the imprint of everything done before.

Another layer was the fylgja, the follower spirit. This being was often seen as a guardian or spiritual reflection of a person’s character. The fylgja could appear in dreams or even physically, usually in the form of a woman or an animal. Seeing someone’s fylgja was often a sign of looming change. In some sagas, the fylgja warns of danger or reveals the shape of a person’s destiny. The fylgja was not the soul of the individual, but a mirrored presence tied to their life force. When the person died, the fylgja either vanished or lingered briefly before fading. A strong or troubled fylgja could influence the path a person walked, shaping their encounters, their luck and their choices.

There was also the fetch-like concept of the hamr, the shape or form. The hamr could change in dreams or magical states. Powerful seers or witches could project their hamr into animal form, allowing them to travel or influence events from afar. While not strictly a “soul,” the hamr represented the flexibility of the self. A rigid or weak hamr could limit a person’s fate; a strong one empowered them. Shape shifting, whether literal or spiritual, was part of how some individuals interacted with destiny and the unseen.

The lyke, the physical body, was another layer whose fate mattered. The Norse did not see the body as unimportant. The state of the corpse could influence the fate of the dead. Those burned according to custom passed on smoothly. Those buried improperly risked becoming restless. The body was the anchor of the self, and its handling shaped how other soul-parts moved after death.

Memory was also a layer, not just a passive record but a force in its own right. A person lived on through the memory of family, community and descendants. Being remembered gave spiritual strength. Being forgotten weakened the dead. The Norse believed that fame or good reputation was a kind of immortality. A person with a bright name continued to influence fate long after their death. A person whose memory was spoiled by shame carried a stain that affected their descendants. Memory was part of the soul’s echo, part of what fate carried forward.

There were other subtle layers as well, such as the önd (the breath of life), the óðr (inspiration or spiritual passion), and the slagr (personal habits or tendencies). Each contributed to how the person acted in the world, how they were shaped by fate, and how they shaped fate in turn.

Because the self was made of layers, fate touched each layer differently. Some parts moved on after death. Some parts stayed near the family or land. Some parts dissolved. Some entered the realm of ancestors and returned in the luck of future generations. Fate was not a single pathway because the soul was not a single thing.

This layered understanding explains much of Norse belief about haunting, destiny, good or bad luck, prophetic dreams and the power of personal choice. It shows that the Norse saw the self as dynamic, interconnected and continually shaped by the world. A person was born with certain threads already in place, but through their will, their actions and the strength of their inner parts, they could influence the pattern for themselves and for those who would come after.

How Personal Deeds Could Strengthen or Weaken Fate

In the Norse worldview, fate was not a rigid, locked path. A person was born into a certain shape of life, marked by orlog, influenced by ancestral deeds, and surrounded by inherited luck. But within this structure, the Norse believed a person could alter the force and direction of their own destiny through action. Fate set the conditions. Deeds shaped the outcome.

This idea appears again and again across the sagas, the Eddas and later folklore. A person who acted bravely, honourably and wisely could strengthen the very fabric of their life, gaining greater luck, stronger reputation, deeper support from their kin, and a more powerful hamingja to pass on to descendants. Someone who acted foolishly, cruelly or cowardly damaged their fate, weakening their luck and casting a shadow over their future.

Personal action did not erase what the Norns had set down at birth, but it could amplify or diminish how that fate unfolded. The Norse imagined destiny as something responsive, almost alive, shifting in accordance with how one carried oneself in the world.

Much of this belief comes from the idea that a person’s hamingja, the inherited and personal luck that guided their fortunes, was strengthened through honourable conduct. A generous chieftain, a reliable ally, a courageous warrior or a wise decision maker could build a powerful hamingja that protected them like a spiritual shield. This was not superstition - it was the logic of a society where reputation, ancestral memory, and the approval of both living and dead played a critical role in survival.

Gifts, loyalty, hospitality, oaths, and social bonds were all acts that strengthened fate. Every time a person fulfilled an obligation, faced danger with steadiness or upheld the dignity of their family, their hamingja grew brighter. Saga heroes carry tremendous luck not because they were chosen arbitrarily but because their ancestors and their own choices shaped a powerful spiritual momentum behind them.

Conversely, breaking oaths, showing cowardice, acting dishonourably or manipulating others with malicious intent damaged one’s fate. Such deeds weakened the hamingja, distorted it or caused it to withdraw. A person who repeatedly acted against honour lost the spiritual support that kept their life balanced. Their luck soured, their prospects faded, and their descendants inherited less strength.

One of the clearest examples of personal action shaping fate comes from Egil’s Saga. Egil Skallagrímsson is a man of immense power, but much of that power comes not only from his personal ability but from the strength of his hamingja. He inherits a fierce and heavy ancestral fate, but he also expands it through bravery, poetry, loyalty to friends and relentless pursuit of justice. His life is harsh, but his strength and determination make his fate formidable rather than bleak.

In Grettis Saga, the opposite occurs. Grettir is strong, clever and capable, but he sabotages himself again and again through stubbornness, rash choices, and refusal to listen to wise counsel. His personal deeds weaken his already troubled fate. His hamingja becomes muddled and diminished. Even though he starts with potential, his actions darken the shape of his life until he is doomed to outlawry. The saga makes it clear that fate did not target Grettir unfairly—he worsened his own path through choices that eroded his spiritual strength.

This interplay between destiny and action was central to Norse ethics. The Norse did not believe people were helpless victims of fate. Instead, they believed people were responsible for how they responded to it. Even a difficult or shadowed fate could be met with courage, shaping a story worthy of honour. A bright fate could be dimmed by carelessness or cowardice.

In this moral framework, honour and fate became intertwined. A person with strong honour walked with firmer luck. A dishonourable person invited doom. The sagas often portray disaster not as random tragedy but as the natural outcome of weakened fate brought on by flawed character or reckless choices.

This is why reputation mattered so deeply. Reputation was not empty vanity - it was a public expression of the state of one’s soul parts, especially hamingja and hugr. A strong reputation attracted allies, protection and opportunities. A damaged reputation left a person spiritually exposed.

Even after death, personal deeds continued to shape fate. A person who lived well could pass strong hamingja to their descendants. One who lived poorly might pass misfortune instead. The future of an entire bloodline could be sharpened or blunted by the choices of a single individual.

This concept reveals a worldview in which fate and free will are not opposites but partners. Destiny gives a person the terrain of their life, but personal action determines how they travel across it. The Norse believed that while you cannot choose the path you begin on, you can choose the steps you take, the way you stand, and the legacy you leave behind.

Fate as a Web, Not a Straight Line

To understand how the Norse thought about fate, you must set aside the modern idea of destiny as a fixed road stretching ahead from birth to death. The Norse did not imagine life as a straight line, nor did they picture fate as a single path chosen for a person. Instead, they saw fate as a vast and interconnected web, woven from countless threads laid down by gods, ancestors, the Norns, the land, and the individual’s own choices. It was a system alive with movement, tension and possibility.

This idea is reflected everywhere in the old literature. Time is not rigid; it is fluid. Fate is not a decree; it is a structure that grows. Every decision, every promise, every betrayal, every act of courage or weakness sends ripples across the web. A person is not a passive traveller but a weaver adding new threads as they go. Their life is one strand among many, always crossing others, always shaped by what lies around it.

The web metaphor explains why fate in the sagas feels both powerful and flexible. Major events often seem inevitable, yet how a person meets them is entirely their own. Heroes sense that something heavy pulls on their thread, guiding them toward a great trial or downfall, but they face it with courage or dishonour, shaping the spiritual weight of their story. Fate gives the event. Choice gives it meaning.

This view is clearest in the concept of wyrd, the unfolding of events shaped by what has already happened. Wyrd is not destiny handed down from on high. It is the living result of countless interwoven threads stretching far back into the past. When someone says that wyrd has taken hold, they mean that the weight of the web has grown too strong to resist. The combined force of history, ancestry, oaths and consequences has gathered into a moment where the direction of the pattern becomes clear.

The web of fate also explains why lineage mattered so deeply. A family was not a collection of unrelated individuals; it was a cluster of threads braided tightly together. One person’s honour strengthened the whole. One person’s disgrace weakened everyone tied to them. The actions of an ancestor could pull a descendant’s thread decades later, for better or worse. This is why sagas often open with long genealogies. They are not simple introductions. They show the reader the shape of the web before the story begins.

Even the gods are part of this weaving. Odin seeks knowledge from the Norns precisely because he understands he is caught in the same web as humans. His actions ripple outward, influencing worlds and ages, but even he cannot escape the consequences of his deeds. Ragnarok itself is the final tightening of the web, the moment when the tension built over ages snaps. It is not punishment or injustice. It is the natural outcome of countless threads woven together over cosmic time.

The web model also shows why dreams, omens and visions mattered in Norse belief. They were not random hallucinations but glimpses into other parts of the web, places where threads were gathering, tightening or shifting. A dream of a dead relative might reveal a weakness in the family’s weave. A vision of battle might show the direction in which the threads were pulling. These signs did not command action but offered insight, allowing individuals to step into the unfolding with awareness rather than blindness.

Because fate was a web, the Norse believed deeply in the importance of personal conduct. A person could not control the entire weave, but they could control the strength of their own thread. Honesty, courage, loyalty, generosity and wise speech tightened and brightened one’s strand, making it resilient when the web pulled hard. Cowardice, deceit, cruelty and oath breaking weakened the thread, making it vulnerable to snapping under strain.

This world created a culture that valued agency, responsibility and honour. People knew they would one day face moments shaped by forces beyond their control, but they also knew they carried the power to shape how strong or fragile they would be when that moment came. Fate was not an excuse. It was a framework.

In this way, the Norse held two truths at once: that life is shaped by forces far greater than any individual, and that each person still holds meaningful power within their own sphere. The web moves, but the thread lives.

Fate, then, was not a straight line from beginning to end. It was a living network, vast and shifting, and each person was part of its structure. Their life touched other lives, their choices echoed through time, and their legacy continued long after they were gone. The Norse understood fate not as confinement but as connection. To be part of the web was to be part of something larger than oneself, woven into the great pattern of the world.

The Boundaries of Choice: What Could Be Changed

For the Norse fate was real, powerful and older than memory. But within that fate lay room for human choice. The boundary between what could be shaped and what could not was one of the most fascinating parts of Norse belief. The sagas show again and again that while some events were fixed, many others lay open to influence, and it was a person’s character, will and wisdom that determined how those possibilities played out.

The Norse distinguished between the shape of life and the contents of life. The shape (the length of one’s life, the family one was born into, the major trials that lay ahead, the broad arc of destiny) was set at birth by the Norns. This was orlog, the deep law carved beneath existence. A person could not simply wish away their orlog, nor escape certain defining moments. Some deaths were foretold long before they happened. Some misfortunes were woven into the ancestral weave generations earlier.

But within this fixed structure, choice was not only possible - it was vital. The sagas are full of examples where the fate of a person, family or community shifts dramatically because someone acted bravely, wisely or dishonourably. The Norse believed that although you cannot choose the mountain placed in your path, you can choose how you climb it, how you face it, and what mark you leave upon it.

A person could change their luck. Hamingja, the ancestral fortune passed through bloodlines, was not static. It grew or shrank based on a person’s actions. A generous or courageous person added strength to their hamingja. A deceitful or cowardly one damaged it. This meant that even someone born under difficult conditions could carve out a meaningful place in the world if their deeds were worthy.

Reputation also lay firmly within the realm of human control. A person could be fated to die young but still earn honour that outlived them. The Hávamál makes this clear: the measure of a person’s worth was not how long they lived, but how well they lived. A doomed hero could meet their end with such dignity and ferocity that their fate became a story of triumph rather than tragedy. This kind of transformation was one of the most powerful choices a person could make.

Even relationships played a role in shaping fate. Alliances, friendships, rivalries, marriages and oaths were choices that altered how threads crossed in the web of destiny. A wise alliance could protect a family for generations. A reckless feud could doom one. A person’s social decisions created ripples that influenced not just their own future but the futures of many others. Fate was shaped as much by community as by the individual.

Interpretation of omens and dreams was another realm where choice mattered. The Norse did not see signs as commands but as warnings or hints. How a person responded to these signs could shift the path ahead. Someone who ignored a dream might walk into disaster. Someone who heeded it might avoid it or be prepared to face it. The sagas show characters making decisions based on subtle hints from the unseen world, and those decisions often become turning points in their stories.

Courage itself was a creative force. A person who faced danger with a firm spirit met a different fate than someone who fled or hid. Even when death was unavoidable, courage changed the meaning of the moment. The Norse believed that courage sharpened the thread of life, making it resonate in memory long after the body was gone. This belief gave individuals real power, even in circumstances they could not escape.

But there were clear boundaries. Some things could not be changed. No one could outrun the final moment set for them. No one could erase the ancestral deeds already woven into their line. No one could reshape the deep laws laid by the Norns. Attempts to defy these boundaries usually ended in ruin. In many sagas, those who try to outwit fate end up creating the very conditions that fulfil it.

Yet the limitations of fate did not oppress the Norse. They gave life structure. The boundaries of destiny created a landscape in which human choice mattered intensely. People did not despair at what they could not change; they focused fiercely on what they could. They shaped their legacy, their reputation, their luck and the inheritance they passed down.

To the Norse, the world was neither controlled entirely by destiny nor governed entirely by free will. It was a dance between the two. Fate gave the rhythm. Choice created the steps. The measure of a life was not whether one could escape the shape laid down at birth, but whether one filled that shape with honour, courage and wisdom.

What Could Never Be Changed: Hard Fate

While the Norse believed deeply in personal agency, they also recognised that some parts of life lay far beyond human influence. These were the elements governed by what we might call hard fate - the immovable core of destiny set down by the Norns, rooted in the oldest layers of orlog. Hard fate was the boundary that even gods respected, the fixed points in life’s pattern that no amount of effort, courage or cunning could undo.

Hard fate took several forms. The clearest was lifespan. The Norns were said to set the length of a person’s life at birth, carving it into the invisible pattern of their orlog. No warrior, no king, no sorcerer, and no desperate parent could bargain for more. Death might come through illness, battle, accident or old age, but the final moment was fixed. Many sagas show this belief through the calm way characters accept death when it arrives. Once the time has come, no medicine, magic or pleading can hold it back. The thread has been measured.

Another form of hard fate was ancestry. A person could not choose the family they were born into, nor the weight of the ancestral deeds that shaped their inherited luck. A child born from a line of oath breakers carried a shadowed orlog, while one born into a family of heroes carried a bright one. The individual could work within this framework and improve or worsen it, but they could not erase the foundation itself. The deeds of forefathers lived on, woven permanently into the family’s fate.

Hard fate also governed events of great importance - moments that shaped the course of an age or the destiny of an entire people. These were not personal misfortunes but world turning events, the kind that appear in myth and legend. Ragnarok is the greatest example. The gods knew it was coming. Odin sought knowledge to face it. Thor prepared for it. Freyr accepted his doom. But none of them could prevent it. Ragnarok was part of the deep structure of the world, a necessary transformation rooted in orlog far older than the gods themselves.

Similarly, many sagas describe prophecies that no one can avoid. A king might try to hide a child destined to overthrow him. A hero might flee the place where his death was foretold. But their attempts simply push them into the very conditions that fulfil the prophecy. This is not a cruel joke of fate but an illustration of how hard fate works: once certain threads are woven, they cannot be undone. Every action, even those taken to avoid destiny, becomes part of the path that leads to it.

The manner of death could sometimes shift, but not the fact of it. A man destined to die on a particular day might change how it happens (by blade, by fall, by misstep) yet the date remains fixed. This is why death scenes in the sagas often carry a sense of quiet inevitability. Characters recognise when their thread has reached its end and meet it without illusion.

Hard fate also included certain inherited traits or tendencies. Some families carried deeply rooted patterns of violence, misfortune or conflict. These were not curses in the magical sense but the natural consequences of generations of deeds, grudges and unresolved tensions. A single person might soften these patterns, but they could not fully remove them. The weight of the family weave was simply too old and too deep.

Even the gods, with all their powers, could not escape hard fate. Odin seeks wisdom not to escape destiny but to understand it. Freyr gives away his sword knowing it will lead to his death. Baldr’s doom is unavoidable despite every effort to stop it. The myths are clear: if the highest beings cannot unmake what the Norns have set down, no human can either.

Hard fate was not seen as injustice. It was the natural structure of the world, the shape that made life meaningful. Without fixed limits, courage would be hollow, and honour would have no weight. The knowledge that certain things could not be changed gave strength to choices, urgency to actions and dignity to the way one faced hardship.

But hard fate never removed the importance of choice. Even when the destination was fixed, the journey remained open. A hero might be destined to fall in battle, but whether he fell bravely or in shame was entirely within his control. A family might carry heavy ancestral orlog, but each generation could lighten or darken it through their deeds. Hard fate set the framework. Human will coloured it.

In the Norse mind, the unchangeable parts of fate created the stage on which the drama of life unfolded. They were not punishments but anchors. They reminded people that life was finite, that deeds mattered, and that the legacy left behind was often more important than the length of one’s years.

How Free Will Worked Within a Predestined World

One of the most remarkable aspects of Norse belief is the way they held fate and free will together without contradiction. To us, these ideas can feel like opposites: either life is predetermined, or we have the freedom to choose our own path. But the Norse saw no conflict here. They lived in a world where destiny and choice existed side by side, shaping each other like two forces weaving the same thread.

To them, fate was not a cage. It was a framework. The Norns set the structure of a life - the major events, the time and manner of death, the family into which a person was born, the ancestral luck they inherited and certain trials they were destined to face. These things were fixed, shaped by orlog, the deep law beneath existence. This was the part a person could not escape or bargain away.

But within that structure lay an enormous space for personal agency. The Norse believed that how a person acted within their destiny mattered just as much as the destiny itself. Fate might tell you that you will meet death in battle, but it said nothing about whether you meet it running or standing your ground. Fate might place hardship in your path, but it does not decide whether you face it with grace or bitterness. Fate might give you a troubled lineage, but it does not force you to continue the pattern.

Free will, in the Norse view, existed precisely in how a person met their fate.

This is why the sagas are filled with characters who act boldly even when they know their end is near. Their actions do not change the outcome, but they change the meaning of the outcome. A hero who dies well gains honour that strengthens his family’s luck. A coward who lives longer but acts without integrity damages his lineage. The Norse saw dignity in embracing one’s fate and shaping its final expression through strength of character.

In this way, free will did not defy destiny - it fulfilled it.

Choice also influenced how heavily or lightly fate pressed on a person. The Norse believed that a person could strengthen or weaken their spiritual and ancestral luck through their deeds. A man who upheld oaths, protected his kin, acted with moderation and courage, and spoke truthfully built a stronger hamingja. This personal and ancestral luck meant that even within the framework of fate, life would tend to unfold more favourably.

Conversely, breaking oaths, acting with cruelty or cowardice, or bringing shame upon one’s name weakened the hamingja. Fate would still unfold, but its weight would fall more heavily. The same trials that a strong person might endure could crush someone whose luck had grown thin.

Thus free will was not the ability to escape destiny. It was the ability to shape how destiny felt.

Even small choices mattered. A person’s behaviour built their reputation, and reputation shaped how others treated them. This in turn influenced the opportunities or threats they encountered, subtly shifting the way their fate expressed itself. Fate provided the landscape, but the person decided where to walk, how quickly, and with what attitude.

In the sagas, wise characters navigate this tension with a kind of clear-eyed acceptance. They recognise that there are forces larger than themselves (ancestry, cosmic order, divine will, the weight of past deeds) but they also understand that these forces do not remove their responsibility. Instead, they sharpen it. Knowing that life is short and fate is fixed gives urgency to their choices. It does not paralyse them. It inspires them to live fully.

This perspective also shaped Norse moral thinking. Goodness was not defined by obedience to divine law. It was defined by how a person acted within the constraints of their destiny. Honour grew from courage, steadiness, generosity and loyalty - qualities that could be expressed regardless of one’s fate. A doomed man could be honourable. A blessed man could be dishonourable. Fate did not determine character; character determined how fate was lived.

Free will also meant the freedom to interpret signs and respond wisely. Dreams, omens and prophecies offered glimpses into the unfolding of fate, but how a person used that knowledge was up to them. They could prepare, seek allies, avoid foolish risks or embrace their destiny with readiness. Fate offered the script; free will determined the performance.

This interplay between destiny and choice is perhaps most clearly shown in the gods themselves. Odin knows he will die at Ragnarok. He cannot change that. But his response (seeking knowledge, gathering warriors, preparing for the final battle) is an expression of divine free will. He cannot change the ending, but he can choose how he meets it. His actions define him far more than his fate.

Humans followed the same pattern. A person’s life might be shaped by forces they could not alter, but they still held the pen when writing their own story. Fate set the chapter headings. Free will filled in the pages.

In the end, the Norse did not ask whether life was predetermined or free. They asked a more practical question: given the fate I have, what will I do with it? Their answer was clear. A life’s meaning came not from avoiding death or hardship but from meeting them with dignity. Fate provided the opportunity. Free will provided the proof of character.

Fate in Daily Life: Omens, Dreams and Decision Making

For the Norse, fate was not an abstract concept discussed only by poets or mystics. It was woven into the fabric of daily life. People expected the world to speak to them through signs, dreams, strange moments and sudden intuitions. The unseen was not separate from ordinary experience - it ran alongside it, influencing choices and warning of what lay ahead. Reading fate correctly was considered a form of wisdom, and ignoring its signals was often portrayed as pride or folly.

Omens were one of the most common ways fate revealed itself. Birds, weather, animal behaviour and strange occurrences all carried meaning. A raven flying overhead could signal Odin’s interest or impending battle. An unexpected calm before a storm might be interpreted as the gathering of something fateful. Even the simplest details (like which foot a person stepped out with in the morning) could be taken as a sign of how the day might unfold. These interpretations were not superstition to them. They were part of a worldview where everything was connected and nothing happened without reason.

Dreams were taken even more seriously. The sagas are filled with scenes where characters dream of dead relatives, strange women, animals or symbolic images, and they treat these dreams as messages rather than fragments of imagination. A dead friend appearing in a doorway to warn of danger was considered a genuine visitation. A dream of falling trees, blood in the snow, or a house collapsing could signal upcoming conflict or loss. Dreams were not simply personal - they touched the edges of fate. Many chieftains and warriors had dream interpreters or wise women who helped reveal the meaning behind their visions.

These dreams were often direct. In Njáls saga, Njáll’s wife Bergþóra dreams of a flock of wolves entering the farmyard, tearing at the livestock and filling the house with terror. She understands immediately that this is a sign of approaching violence, a warning from fate itself. In other stories, dreams come in riddles or symbolic echoes. A warrior might dream of forging a broken sword, or a woman might dream of walking barefoot through snow that melts behind her. These images demanded interpretation. The Norse believed that fate rarely speaks plainly, but it always speaks with intention.

Some individuals were known for their gift of insight. Certain families were believed to produce dreamers, people whose visions consistently proved true. A person might be said to have a sharp hugr, a keen inner mind that could sense the movement of events before they became visible. Others relied on volur or seers, specialists trained in the vast symbolic language of fate. These women, often wandering prophetesses or respected members of a household, were consulted when decisions had serious consequences: marriages, feuds, voyages, battles or legal disputes.

Decision making among the Norse rarely happened without some reference to fate. Before a voyage, men watched the wind, the flight of birds, the shape of clouds. If omens were poor, even the most determined crew might hesitate. Before battles, warriors read the mood of the land, listened for prophetic sayings and looked for signs in the behaviour of their horses or weapons. If a spear fell from someone’s hand, or if a sword slipped from its sheath unexpectedly, it might be taken as a warning. These were not irrational fears—they were part of a world where the boundary between the natural and supernatural was thin.

Even in legal matters, fate played a role. Lawspeaker decisions were sometimes influenced by dreams or omens. A man's testimony could be strengthened or weakened by a prophetic dream. In a culture without written scripture or divine commandments, signs from the world around them carried real authority. Fate was not just cosmic; it was practical.

Yet these signs did not remove free will. They simply informed it. A man might receive a warning and choose to go forward anyway. A family might dream of trouble but decide to stand firm. Many heroes in the sagas deliberately walk into their foretold doom because honour demands it. Fate could guide, but it did not command. The Norse saw wisdom in listening to omens, but they also recognised bravery in acting despite them.

The presence of omens also reinforced the idea that fate was not random. Events were not isolated accidents but part of a larger pattern. The world was constantly communicating - through weather, animals, dreams, sudden feelings, or the behaviour of everyday objects. People who noticed these signs were considered thoughtful and perceptive. Those who ignored them were sometimes mocked or judged as short sighted.

Some signs were so widely recognised that they became part of cultural instinct. If a weapon rang without cause, if a voice was heard calling someone’s name when no one was there, if a dead relative appeared in a dream with a troubled expression - these were taken as indicators that fate was shifting. And when fate shifted, people adjusted their choices accordingly.

In everyday life, fate was less a distant power and more a quiet companion. It walked beside people, whispered in the wind, stirred in the embers, visited in sleep and revealed itself in the smallest details. Anyone could sense it, but not everyone could interpret it.

Through omens and dreams, the Norse lived with a constant awareness that life’s events were part of a much larger weave. This awareness shaped their decisions, their courage and their acceptance of whatever came. Fate was not something that happened only at the end of a life. It was present every day, guiding the steps that would ultimately lead a person to their destined end.

The Norse View of Chance vs Purpose

To the Norse mind, nothing in life was truly random. What we might call coincidence, luck or chance was, to them, the surface appearance of deeper forces at work. The world was thick with intention. Events unfolded according to patterns woven long before the moment they were experienced. Even when life felt unpredictable or chaotic, the Norse assumed there was a purpose behind it, rooted either in personal orlog, ancestral consequence, or the wider structure of the cosmos.

This does not mean they believed everything was predetermined in a rigid, fatalistic sense. Rather, they saw the world as layered, with visible events shaped by invisible causes. A person tripping in the road, a sudden illness, the arrival of a stranger, a lost object, a weapon breaking in battle - none of these were dismissed as simple accidents. Each was understood within the wider context of fate and consequence. Something had set them in motion, whether the person could see it or not.

One of the clearest examples is the concept of hamingja, the personal and ancestral luck that could rise and fall based on deeds. If a man’s fortunes suddenly improved or worsened, the Norse did not shrug and say it was random. They traced it to shifts in this inherited spiritual force. Good fortune indicated a strong, bright hamingja. Misfortune suggested that something had weakened it - perhaps a broken oath, an unresolved feud, or the lingering weight of ancestral wrongdoing. Chance, in this worldview, was often a reflection of spiritual balance.

This sense of purpose extended to major life events. Marriages, feuds, births and deaths were all viewed as carrying the weight of deeper forces. A child born under strange circumstances might be considered the bearer of ancestral fate. An unexpected meeting between two families might be interpreted as the reawakening of an old obligation. When people crossed paths at the right or wrong moment, it was rarely seen as mere coincidence. Fate worked through these encounters, pushing lives into alignment or collision.

Yet the Norse were not puppets of unseen forces. Their sense of purpose did not erase agency. Instead, it gave individuals the responsibility to act wisely within a purposeful world. If something happened, the question was not “why did this random event occur?” but “what does this event mean?” and “how should I respond?” The world was full of signals, but it was up to each person to interpret them and act accordingly.

Dreams, omens and signs were part of this worldview because they revealed purpose more clearly than everyday events. A raven circling overhead, a sudden silence in a hall, the behaviour of animals, or a dream of blood and fire were seen as glimpses behind the curtain of visible reality. These signs were not random flashes. They were messages from a world where past, present and future were woven together.

Even loss and tragedy were framed through this lens. When someone died young or suffered repeated hardship, the Norse did not assume it was meaningless misfortune. They looked for the deeper cause - perhaps an inherited doom, a Norn’s marking at birth, a broken promise, or an unresolved feud. This gave suffering a kind of structure. Pain was not senseless; it was part of the world’s accounting.

Chance did exist, but in a limited, surface-level way. It was the appearance of randomness when the reasons behind events were hidden or too complex to perceive. To the Norse, what we call chance was simply purpose unseen. The world was filled with forces (ancestral, spiritual, cosmic) that shaped outcomes. Humans witnessed only the tip of that vast system, so events could appear sudden or unconnected.

Purpose also shaped courage. If life contained no randomness, then fear of the unknown held less power. People could act boldly, trusting that their fate was already woven and that no accident could steal from them what was not theirs to lose. This belief is why saga characters walk into danger with calm acceptance. They do not fear the unpredictable, because the unpredictable is an illusion. The deeper truth is that everything has a place within the weave.

This worldview also fostered a strong sense of responsibility. Because actions shaped future consequences, people understood themselves as participants in the unfolding of fate. A careless choice could have far reaching effects. A moment of bravery could change the course of a family’s fortune. Purpose gave weight to every decision.

In the end, the Norse lived in a world where the visible and invisible danced constantly. What looked like chance was simply purpose in disguise. What looked like luck was the reflection of deeper spiritual forces. What looked like coincidence was the touch of ancestral threads pulling lives together. For them, life was not random. It was meaningful, even when the meaning could not yet be understood.

How Christianity Altered Norse Ideas of Fate

The coming of Christianity to Scandinavia did not simply change religious belief; it transformed the entire framework through which people understood fate, choice and the forces shaping human life. The old Norse worldview was built upon a layered, impersonal system of destiny woven from ancestral deeds, cosmic law and the work of the Norns. Christianity introduced a very different structure: a single all powerful God, divine judgment after death, sin and salvation, and a moral universe where intention mattered as much as action.

These two systems did not blend smoothly. For several generations, they lived side by side, creating a hybrid world that shows up clearly in the later sagas, law codes and folklore.

In the pre Christian world, fate was older than the gods. It was not a punishment or reward; it simply was. Bad things happened because of tangled orlog, ancestral misdeeds, powerful emotions at death, offended spirits, or the natural movement of the web of wyrd. Christianity introduced the idea that misfortune could be the result of divine will, moral failing or the work of demons. This was a major shift. The Norse did not previously imagine suffering as divine punishment. Fate was not moral. Christianity made it moral.

Under the old system, the dead could linger in dreams, walk as revenants, or influence the living through hamingja and family guardians. Christianity attempted to suppress these beliefs, but they proved stubborn. Instead of disappearing, they changed form. Ghosts became restless souls in need of prayers. Ancestral spirits became interpreted as demons or the tormented dead. Revenant tales survived, but writers added Christian explanations such as improper burial rites or ungodliness. The old idea of spiritual layers within the person was gradually replaced by a single soul judged by God.

The Norse believed that certain deaths were fixed and unavoidable. Christianity introduced the concept that prayer, repentance or divine mercy might change one’s fate. This conflicted with the older belief that lifespan was set at birth, unalterable even by the gods. Over time, Christian concepts softened the sharp finality of Norse fate. People increasingly believed that illness, death or disaster might be averted through holy intervention rather than simply endured with stoic acceptance.

Personal responsibility also changed. In the Norse worldview, deeds shaped reputation, ancestral luck and the tone of one’s fate, but the gods did not judge behaviour after death. Christianity introduced a linear moral afterlife: heaven or hell. Suddenly, intention, inner thoughts and moral purity mattered more than honour or the balance of consequence. A man could no longer rely on bravery and generosity alone. He was now judged for pride, lust, anger and doubt - things the Norse had treated very differently. A person’s eternal fate was now determined by divine judgment, not the weave of wyrd.

The Norns, once central figures in shaping destiny, faded from religious life. Christian scribes often reduced them to vague “fates” or reinterpreted them as witches or prophetic women. Their cosmic authority was replaced by God’s will. Orlog, the deep law beneath existence, was overshadowed by providence, the Christian idea that God actively guides events toward an ultimate plan. Yet echoes of the old belief remained. Icelandic sagas sometimes describe a character’s fate with Christian language, even as the events follow the old fatalistic pattern.

Decision making also changed. Where once people read omens, dreams and signs from the land, Christians were encouraged to trust scripture, priests or saints. Dream visitation from the dead became problematic, often interpreted as temptation or demonic trickery. Yet many continued to believe in such dreams privately, and the sagas preserved them with only light Christian framing. The web of meaning through nature, spirits and ancestral presence became replaced by the idea of divine messages or spiritual warfare.

Even luck changed its nature. Hamingja had been a tangible, inherited force that responded to honour and action. Under Christianity, luck became providence, divine favour or blessing. Misfortune could now be seen as God’s testing or punishment. The impersonal balance of the old world became personal and moral. This shift began to reshape how people understood responsibility for events. Under the old belief, a streak of bad luck might be an ancestral burden. Under Christianity, it might be interpreted as God calling someone to repentance.

Despite these changes, elements of the old worldview persisted stubbornly into later folklore. Families continued to speak of inherited “luck” or “strength” in ways that resemble hamingja. Burial customs retained hints of old fear of revenants. Dreams of the dead remained powerful in folk stories. Even the concept of unchangeable “doom” lingered, though now softened by the possibility of divine intervention.

Ultimately, Christianity did not erase Norse ideas of fate; it reshaped them. The impersonal, woven web of wyrd became a moral, intentional plan governed by a single deity. The Norns’ cosmic authority was replaced by divine judgment. Yet the deep northern instinct that life follows patterns older and larger than the individual never disappeared. It simply found new language.

Fate in Later Scandinavian Folklore

Long after the ‘Viking Age’ ended, after the temples fell and Christianity reshaped the North, the old sense of fate did not disappear. It simply slipped into new forms. Scandinavian folklore, collected centuries after conversion, still carries unmistakable echoes of the ancient ideas: inherited luck, prophetic dreams, guardian spirits, doom bound families, and the quiet certainty that life unfolds according to patterns older than memory. These stories, told around hearths and farmsteads, preserved the deeper instincts of the Norse worldview even while their religious language changed.

One of the clearest survivals is the belief in family luck. In rural Norway, Iceland and Sweden, people spoke of certain families having strong luck, heavy luck or dark luck. This was not mere fortune telling - it was hamingja disguised under new words. A prosperous family was said to have good luck walking ahead of them; a troubled one was said to carry old burdens that clung to their descendants. Even into the nineteenth century, Scandinavians quietly acknowledged that children inherited more than land or temperament - they also inherited spiritual momentum.

Another echo lies in the figures of female guardian spirits. Long after belief in the dísir faded as a recognised pagan practice, people still told stories of house guardians, ancestor women who protected the farm, or mysterious female presences who helped or warned families. In Sweden, the vättar and tomtar often acted like domestic spirits who shaped the household’s fate, rewarding respect and punishing neglect. In Icelandic folktales, ancestral women appear in dreams to give warnings before storms or family disasters. These beings are not named Norns or dísir, but they carry their essence: feminine, protective, tied to lineage, and deeply entwined with the unfolding of fate.

Dreams retained their power as windows into destiny. Rural folk placed strong trust in dream warnings, dream omens and dream visitations from the dead. The old sagas treated dreams as messages from the weave of fate; folk tradition preserved that instinct almost untouched. A dream of broken tools, falling snow, or a cow giving birth at the wrong time was enough for a farmer to delay a journey or prepare for hardship. People believed that the dead spoke through dreams more easily than through waking signs, a belief that reaches directly back to the hugr and fylgja traditions of earlier centuries.

There is also the enduring concept of the efterganger, the again-walker, a clear descendant of the draugr. Though Christianity tried to reinterpret revenants as demons or condemned souls, folk tales stubbornly remembered them as the dead who returned because something in life was unresolved. In Norwegian stories, restless spirits often linger near their burial mounds or haunt crossroads. In Icelandic folktales, walking corpses guard treasure, settle scores, or wander as cold, heavy figures until the living intervene. These beings are less monstrous than the draugar of the sagas, but they carry the same core idea: death does not always end one’s involvement with the world.

The belief in prophetic weaving also survived. In some Swedish traditions, fate was said to be spun by three white-clad women who appear at the birth of a child. These birth spirits, sometimes called nålänglor or lykkefinner, bless or mark the newborn in ways reminiscent of the old Norns. Christianity tried to frame them as angels or fairy-like beings, but their actions are unmistakably tied to the ancient role of allocating destiny. Their presence at the cradle is a softened echo of the powerful birth Norns of earlier belief.

Folk practices also reveal persistent ideas about unavoidable destiny. Certain deaths were spoken of as förutbestämd, predetermined. A family might say that a person had gåt sin tid, gone in their proper time. Others spoke of dödsomen, the omen of death, where a sound, a shape or a dream foretold an inevitable loss. These ideas are nearly identical to the saga notion that some deaths cannot be prevented, only met with readiness.

At the same time, people believed that one could strengthen or weaken their fortune through behaviour - kindness to spirits, honesty in dealings, fulfilling promises, or maintaining harmony in the household. This mirrors the old belief that a person’s deeds influence the brightness of their hamingja. Christianity reframed these actions in moral terms, but the old underlying logic remained: the world responds to how you carry yourself.

Another important survival is the land’s role in fate. Folklore across Scandinavia speaks of places that hold power: hills, rocks, streams, crossroads and ancient burial sites. Disturbing these places could bring misfortune. Showing respect (by offering milk to the tomte or avoiding forbidden ground) could keep the land’s luck favourable. This echoes the Norse belief that fate was tied to landspirits, the hidden people, and the deep memory of place. The land itself was part of the weave, and treating it well ensured smoother destiny.

Finally, folklore preserved a softer version of the old tension between fate and free will. People believed that certain events in life were meant to happen, but they also insisted on personal responsibility. A farmer might say that misfortune was fated, but he would still work harder the next year to improve his luck. A sailor might dream of drowning and still venture out to sea, determined to face whatever came. This balance (accepting some things as inevitable while still acting with determination) is pure Norse philosophy, carried quietly through the centuries.

In the end, Scandinavian folklore shows that the old Norse understanding of fate did not vanish with the rise of Christianity. It simply adapted. The Norns became unnamed birth spirits. Hamingja became family luck. Dreams remained messengers. The dead continued to walk. Fate remained a web, though now threaded through with new symbols. Beneath the Christian surface, the heartbeat of the old worldview continued, steady and unmistakable.

Modern Misunderstandings About Norse Destiny

The idea of Norse fate has enjoyed a huge revival in recent years, but with that revival has come a wave of misunderstandings. Modern people often approach the concept with assumptions formed by later religions, fantasy fiction or pop culture rather than by the worldview of the old North. As a result, the Norse understanding of destiny is usually simplified, moralised or mistaken for something it never was. To recover the real meaning of fate in Norse belief, we must clear away these modern misconceptions and look again at the ideas preserved in the sagas, the Eddas and later folklore.

One of the most common misunderstandings is the belief that the Norse saw fate as fixed in every detail, a rigid script where every moment is predetermined. This is closer to Greek tragedy or certain strands of later theology than anything found in the North. Norse fate was layered and dynamic. Certain events were unchangeable (particularly one’s ultimate death) but a vast amount of life’s movement depended on personal deeds, inherited luck and the choices one made within the shape one had been given. This mixture of inevitability and agency is subtle, and modern readers often flatten it into one extreme or the other.