The Codex Regius - Poetic Edda

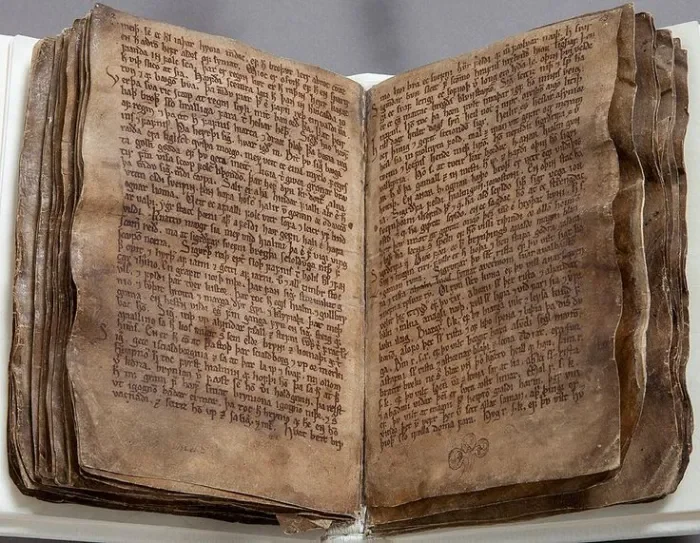

The Codex Regius is a manuscript of 45 surviving leaves, written in a single scribal hand around 1270 - 1280 in Iceland. It originally contained 53 leaves but eight are now lost, creating what scholars call the Great Lacuna.

The script is a Gothic book hand, typical of Icelandic ecclesiastical writing. Despite its modest appearance, it preserves the only copy of many of the most famous Old Norse mythological poems.

Discovery and Early History

The Codex Regius is one of the most remarkable medieval manuscripts to survive from the Norse world, and its origins remain surrounded in mystery. It is thought to have been written by unknown scribes sometime in the second half of the 13th century, though the material it contains is certainly much older. Many scholars believe that the Codex is not the original form of these poems at all, but rather a copy of earlier collections, themselves possibly transmitted orally for generations before being committed to parchment. This theory is supported by the style and outlook of certain poems within the manuscript: some verses contain a tone and imagery that feel strikingly “modern” compared to their surrounding material, suggesting that interpolations or editorial adjustments may have been introduced as the texts were copied and re-copied. In other words, the Codex Regius may represent both the preservation of ancient tradition and the traces of scribal interpretation from a later medieval world.

The manuscript came to light in 1643, when it was rediscovered by Bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson of Skálholt, one of Iceland’s foremost churchmen and scholars. Believing that he had uncovered the long-lost work of the famous Icelandic priest and scholar Sæmundr fróði (Sæmundr the Learned), Brynjólfur gave the manuscript the name Sæmundar Edda. Although we now know this attribution was incorrect, the title lingered in both scholarly and popular imagination for centuries, contributing to the Codex’s aura of mystery and antiquity.

In 1662, Brynjólfur presented the manuscript as a gift to King Frederick III of Denmark, a gesture that cemented its importance but also began a long period of absence from Iceland. The manuscript was given the Latin name Codex Regius (The King’s Book) in honour of its royal owner and placed in the Royal Library in Copenhagen, where it remained for more than three hundred years.

The significance of the Codex Regius for the study of Norse mythology cannot be overstated. It is the single most important source for the eddic poems, the anonymous mythological and heroic lays that preserve the mythic universe of the pre-Christian North. Without the Codex, masterpieces such as Völuspá (The Prophecy of the Seeress), Hávamál (The Sayings of the High One), and Þrymskviða (The Lay of Thrym) might have been lost forever. Unlike Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda, composed around 1220 as a handbook for poets, the Codex Regius preserves the raw poetic corpus itself in traditional alliterative verse. It thus provides a rare and direct glimpse into the worldview, ritual, and imagination of the ‘Viking Age’ and its aftermath.

For centuries, Icelandic scholars and the public longed for the return of this national treasure. That moment finally came on April 21, 1971, when the manuscript was ceremonially repatriated. Transported aboard the Danish naval vessel Vædderen, it arrived in Reykjavík harbor to immense celebration, greeted by thousands of Icelanders who saw in its return a symbolic act of cultural restoration and independence. Together with Flateyjarbók, another great medieval Icelandic manuscript returned soon after, it marked the beginning of a long and carefully negotiated process of manuscript repatriation between Denmark and Iceland.

Today, the Codex Regius is housed at the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies in Reykjavík, where it continues to inspire scholars, poets, and readers around the world. It is not only a cornerstone of Old Norse literature but also a cultural symbol of Iceland’s enduring connection to its medieval heritage.

Contents of the Manuscript

The Codex Regius is divided into two broad thematic sections:

Mythological Poems,

first half of Codex Regius (Goðakvæði) -

Vǫluspá (The Seeress’s Prophecy)

Hávamál (Sayings of the High One)

Vafþrúðnismál (The Lay of Vafthrúdnir)

Grímnismál (The Lay of Grímnir)

Skírnismál (The Lay of Skírnir)

Hárbarðsljóð (The Lay of Hárbarðr)

Hymiskviða (The Lay of Hymir)

Lokasenna (Loki’s Quarrel)

Þrymskviða (The Lay of Thrym)

Vǫlundarkviða (The Lay of Vǫlundr)

Alvíssmál (The Lay of Alvíss)

Heroic Poems,

second half of Codex Regius (Hetjukvæði) -

Helgakviða Hundingsbana I (First Lay of Helgi Hundingsbane)

Helgakviða Hjǫrvarðssonar (Lay of Helgi Hjörvarðsson)

Helgakviða Hundingsbana II (Second Lay of Helgi Hundingsbane)

Frá dauða Sinfjǫtla (On the Death of Sinfjötli) [short prose]

Grípisspá (The Prophecy of Grípir)

Reginsmál (The Lay of Regin)

Fáfnismál (The Lay of Fáfnir)

Sigrdrífumál (The Lay of Sigrdrífa)

Brot af Sigurðarkviðu (Fragment of a Lay of Sigurd)

Guðrúnarkviða I (First Lay of Guðrún)

Sigurðarkviða in skamma (Short Lay of Sigurd)

Helreið Brynhildar (Brynhild’s Ride to Hel)

Dráp Niflunga (The Slaying of the Niflungs)

Guðrúnarkviða II (Second Lay of Guðrún)

Guðrúnarkviða III (Third Lay of Guðrún)

Oddrúnargrátr (The Lament of Oddrún)

Atlakviða (The Greenlandic Lay of Atli)

Atlamál in grœnlenzku (The Greenlandic Poem of Atli)

Guðrúnarhvöt (Guðrún’s Incitement)

Hamðismál (The Lay of Hamðir)

The Great Lacuna

The missing 8 leaves (the Great Lacuna) occur after Sigrdrífumál and likely contained the longer Sigurðarkviða (sometimes called in meiri) along with further material on Brynhildr and Sigurðr’s death [Great Lacuna; Sigrdrífumál]. Without these, our knowledge of the Sigurðr cycle is fragmented, forcing scholars to rely on prose sources like Völsunga saga for reconstruction.

Read more about The Great Lacuna here! >

Importance for Scholarship

The Codex Regius is the key to everything we know as the Poetic Edda. It is the only surviving medieval manuscript that keeps the Eddic poems together as a full collection, rather than in scattered pieces. A few verses and stanzas appear in other places (like in sagas, in Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda, or in later paper copies) but no other manuscript gives us the same depth or continuity. Because of this, the Codex is the main source against which every other text is compared. Without it, the very idea of a Poetic Edda would hardly exist.

For scholars, the Codex has many different uses and touches nearly every part of Old Norse studies.

Reconstructing Norse myth: The Codex preserves key poems such as Völuspá (the prophecy of the seeress about creation and Ragnarök), Hávamál (Odin’s wisdom sayings), Vafþrúðnismál (a riddle contest about the cosmos), and Þrymskviða (the story of Thor recovering his stolen hammer). These survive most fully only here. Without the Codex, our picture of Norse mythology would be broken and incomplete. Thanks to it, we can see the whole story of creation, the values of the gods, and the final destruction of the world.

Checking Snorri: Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda (c. 1220) is another major source, but Snorri was a Christian writer who organized myths in his own way. The Codex lets us compare Snorri’s version with older poems, showing where he simplified, changed, or reshaped the myths. This helps us see the gap between the older oral traditions and later medieval retellings.

Poetic form & orality: The poems in the Codex are written in traditional verse forms like fornyrðislag (old story meter) and ljóðaháttr (song meter), which carry the rhythm of spoken poetry. Because the Codex brings many of these poems together, scholars can study repeated themes, stock phrases, and storytelling patterns. Things like wisdom contests, boasting duels, and prophetic speeches all point to a living oral tradition behind the written text.

Language & vocabulary: The Codex preserves a wide range of early Icelandic words, including legal terms, ritual phrases, kennings (poetic metaphors), and proverbs. Many of these words are rare or appear nowhere else, making the manuscript a kind of time capsule of medieval language. Linguists use it to study how the language developed, and to compare it with other Indo-European traditions.

Heroic legend: The second half of the Codex focuses on heroic poetry, especially the Völsung–Nibelung cycle. These stories about Sigurd the dragon-slayer, Brynhild, Guðrún, Atli, and their families connect to legends found across Europe, from Old German to Anglo-Saxon to later Scandinavian ballads. The Codex gives us the Norse version of this shared heroic tradition, which would otherwise be missing from the picture.

Missing leaves and editing: The Codex once had 53 leaves, but eight are now missing, a gap known as the Great Lacuna. Because of this, editors must rely on other sources (later copies and related texts) to guess what was lost. This makes the Codex central to how scholars study manuscripts, scribes, and the way texts were passed down.

In short, the Codex Regius is not just an old book - it is the foundation of Norse mythology as we know it. Without it, there would be no Poetic Edda, no clear picture of the mythic world, and only faint traces of the great heroic tales. Its survival gives us a rare and precious window into the beliefs and stories of pre-Christian Scandinavia.

Symbolic Significance

For Iceland, the Codex Regius is far more than just an old manuscript. It is a national treasure and cultural emblem, carrying meanings that go beyond its parchment pages. The poems inside preserve a worldview from before Christianity, yet they were copied down in a Christian age. This dual character (pagan stories written in a Christian script) ties together the deepest layers of Iceland’s past. Today, housing the Codex in Reykjavík means that ancient traditions are not only remembered but also woven into the modern identity of the nation.

The return of the Codex in 1971 was seen as an act of restoration, both cultural and emotional. After centuries in Copenhagen, the manuscript finally came home aboard the Danish naval vessel Vædderen. The event was marked by great celebration, with Icelanders welcoming back a piece of their heritage that had been out of their hands for more than 300 years. Its return was not just the delivery of a book, but the reclaiming of a voice - a reminder that Iceland could once again care for the stories and wisdom of its ancestors on its own soil.

Since then, the Codex Regius has played a central role in education and public life. It is displayed in exhibitions, reproduced in facsimiles, and studied in schools, allowing new generations to encounter the old poems directly rather than only through later retellings or adaptations. For both Icelanders and international visitors, the manuscript offers a tangible connection to Norse myth in its earliest surviving form. It is not just literature - it is lived heritage.

At the same time, the history of the Codex also represents shared stewardship between Denmark and Iceland. The careful planning of its transfer, the ongoing cooperation between institutions, and the attention given to its conservation show that cultural treasures survive through both international trust and national pride. Its story is therefore not only about ownership but also about collaboration and respect between nations.